Fuente: The Washington Post – By Douglas MacMillan

Before approving plans for a new jetliner called the 737 Max, Boeing’s board of directors discussed how quickly and cheaply it could be built to compete with a rival — but the members didn’t ask detailed questions about the airplane’s safety, according to three people present for the meetings.

“Safety was just a given,” said one former board member, speaking on the condition of anonymity because the 2010 discussions were confidential.

When a 737 Max operated by Lion Air crashed off the coast of Indonesia last year, board members learned for the first time about a Boeing software system that pushed the plane’s nose downward — but they didn’t see enough evidence of a software malfunction to ground the entire fleet of more than 300 jets.

“It looked like an anomaly,” Boeing board member David Calhoun said.

A second plane crash, involving an Ethiopian Airlines jet in March, erased that theory.

The decision-making of Boeing’s board — an elite club of corporate titans and government dignitaries — is under scrutiny after two crashes of the 737 Max killed 346 people in the span of five months. Shareholders and families of the crash victims are pushing directors to share what they knew about the jet’s safety and whether they could have done more to prevent the accidents. Boeing has acknowledged that in both incidents the planes’ noses were pitched downward by a software system called MCAS.

In the first on-the-record interview of a Boeing board member since the crashes, Calhoun, who joined the board in 2009 and became its lead director last year, defended his group’s decision to keep the planes in the air. “I don’t regret that judgment,” he said. “And I don’t think we got it wrong at that time and that place.”

A corporate board of directors serves on behalf of the shareholders, hiring and firing the chief executive, setting the pay of top executives and questioning whether their decisions are serving the company’s long-term interests. “They set up guardrails for the CEO,” said James Schrager, a management professor at University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business.

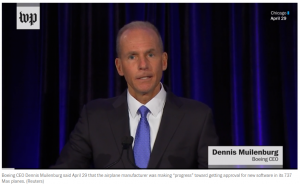

At Boeing, CEO Dennis Muilenburg enjoys strong support from the board. Muilenburg, a longtime Boeing engineer who rose through the ranks of its defense business, was the safe choice to succeed James McNerney when he stepped down as CEO in 2015. With Muilenburg at the helm, the company’s stock price has tripled over three years. When McNerney left the board, Muilenburg was given the powerful dual role of chairman — head of the board — and CEO.

With the company now facing one of the most tumultuous episodes in its history, critics are asking what guardrails the board has set. Throughout the history of the 737 Max, the board has appeared to move in lockstep with company’s leaders.

When the 737 Max was built, the board should have asked tough questions about how the plane’s safety was tested, said Charles Elson, director of the John L. Weinberg Center for Corporate Governance at the University of Delaware. “Directors are not there to stick their fingers in the design of the aircraft,” Elson said. “They are there to assure themselves that the processes by which the aircraft was designed were effective and safe.”

Boeing could have prevented a second tragedy if it had grounded the 737 Max after the first crash, said Tom Demetrio, a lawyer who is suing Boeing on behalf of the families of the Indonesia crash victims. “The Ethiopian aircraft should have never even been allowed to take off,” Demetrio said. “Boeing, not knowing why the Lion Air crash occurred, should have said, ‘Everybody out there, stop flying these damn things.’”

None of the government bodies privy to the details of the Lion Air investigation called for a grounding of the jets before the second crash.

In the days following the Ethiopia crash, the board quickly reversed its position on grounding the fleet. First, amid a global uproar, Muilenburg called President Trump and asked him not to ground the planes. A day later, after a call with his board, Muilenburg called Trump to urge reversing course and recommend a grounding order, as Boeing tried to get ahead of a likely directive from the Federal Aviation Administration, according to a person familiar with the matter who spoke on the condition of anonymity because they weren’t authorized to disclose private conversations.

The reputations of Boeing’s board members are at stake. Investor advisory group Glass Lewis recently recommended that shareholders vote to remove one director, former Continental Airlines CEO Lawrence Kellner, because the audit committee he oversees “should have taken a more proactive role in identifying the risks associated with the 737 Max 8 aircraft.” Kellner was reelected.

Members of Boeing’s board of directors. (Getty Images, AP and The Washington Post)

Members of Boeing’s board of directors. (Getty Images, AP and The Washington Post)

In interviews, Kellner and Calhoun both said that the board was never briefed on the MCAS software before the Lion Air crash and that they don’t see it as part of their job to inspect every technical feature on an airplane. Kellner, who became a director in 2011, said he and other board members are now working to understand whether there were questions they should have asked about the plane’s safety sooner.

“We should review our process, which we are,” Kellner said. “I think everyone should look back and say, ‘What can we do to strengthen this process?’”

A growing number of Boeing investors believe Muilenburg has too much influence over the board. At the company’s annual investor day, on April 29, one out of three shareholders supported a proposal to restructure the board with an independent chairman — a board member with more authority to challenge the CEO. Boeing argues that its lead director, Calhoun, has the power to set the agenda of board meetings and consult with directors on the performance of the CEO.

The proposal didn’t pass, but it earned a higher portion of votes than a similar measure last year. Boeing’s spokesman declined to make Muilenburg available for an interview.

Calhoun said the board has considered having an independent chairman, and recently discussed the matter with some of the company’s largest institutional investors. However, following the recent shareholder vote rejecting the measure, he said he’s “confident we are in the right place” on governance.

A plum assignment

A seat on Boeing’s board is a prestigious job with great pay. Each director is paid an average of $324,000 in cash and stock annually — the 29th-highest board pay in a recent survey of the 100 largest companies by compensation researcher Equilar. Boeing flies board members to Chicago or another city with Boeing facilities for a one-day meeting every other month; they typically arrive Sunday afternoon and leave by Monday afternoon.

The current lineup of 13 directors includes Lynn Good, CEO of Duke Energy; Robert Bradway, CEO of biotech giant Amgen; and the former chiefs of Allstate, Medtronic, Aetna and Nortel. Caroline Kennedy, the former U.S. ambassador to Japan and daughter of John F. Kennedy, joined in 2017.

Nikki Haley — who opposed efforts by Boeing employees to unionize in South Carolina when she was governor of the state — joined the board last month. A spokeswoman for Haley did not respond to requests for comment.

At the beginning of this century, Boeing directors helped steer the company through scandals by ousting two successive CEOs: Phil Condit was pushed to resign in 2003, after an investigation found his team violated ethics rules by promising a job to a government procurement officer; Harry Stonecipher was forced out in 2005, following the discovery of his extramarital affair with a Boeing employee.

In a statement at the time he resigned, Condit said he feared the controversy “bogged down” the company. Stonecipher didn’t comment at the time.

Boeing’s next leader, McNerney, became the first executive to start his tenure at the company with the three titles of president, chairman and CEO, giving him broad authority over decision-making. McNerney, a former GE executive with a wide network, recruited allies such as Calhoun, his former GE colleague, to the board.

McNerney declined to comment through a Boeing representative.

During a series of meetings in 2010 and 2011, Boeing’s board discussed how the company should respond to the threat of a new, more fuel-efficient line of Airbus jets, the people present at those meetings said. Several directors worried that a new plane would be too costly and take too much time to bring to market, especially since Boeing was at that time over budget and years past its deadline for launching the 787 Dreamliner, people who were present at the meeting said. The board talked about how it would be faster and cheaper to revamp an older version of a Boeing jet.

The plan to revamp an older 737 jet included larger engines mounted farther up on the wings, which altered the plane’s balance. Boeing engineers designed the MCAS software to compensate for this imbalance. In both crashes, investigators believe an instrument called an angle-of-attack sensor fed the MCAS software bad data, causing it push the planes’ noses downward. The final causes for both crashes have not been determined.

One challenge for board members is a lack of technical expertise. John H. Biggs, a former CEO of the TIAA-CREF insurance company, was a Boeing director during some of the discussions around the 737 Max and doesn’t remember anyone in that group questioning whether a reconfiguration of the 737 with larger engines would create trade-offs that would affect safety.

“The board doesn’t have any tools to oversee [safety],” Biggs said. “The FAA doesn’t seem to be able to figure out what’s safe. So how do you expect the board members to be able to do that?”

Some corporate boards, such as JetBlue and Dow Chemical, mandate safety oversight in their bylaws, seeing it as a part of their duty to manage risks. Boeing’s corporate governance principles do not mention the word “safety,” and its board does not include any experts in airplane safety.

Calhoun said Boeing’s board always looks at whether a new or reconfigured plane is the best solution when considering a new addition to its fleet. Calhoun said it doesn’t make sense for a board to be filled with aviation or safety experts. Instead, he says, the group relies on the expertise of each director. Kellner can speak to the needs of airline customers; Calhoun knows how to manage suppliers, from his time at airplane engine maker GE. He also said the board got routine updates on Boeing’s certification process with the FAA.

“Do we make sure that the rigor around those processes are good and that they are reported to us step by step? Of course we do,” Calhoun said. “Do we go down to the test site and watch the monitors to find out whether they’re working accurately? No, we don’t.”

Boeing’s board was also counting on the company’s strong safety track record. Across all models of Boeing 737 planes, a fatal crash has happened 0.23 times in every million flights, according to data compiled by AirSafe.com.

A spokesman for the FAA pointed to recent testimony by the agency’s acting administrator, Daniel Elwell, who defended the strong safety record of U.S. commercial flight in recent decades. “Since 1997, the risk of a fatal commercial aviation accident in the United States has been cut by 95 percent,” Elwell told a Senate subcommittee. “And in the past 10 years, there has only been one commercial airline passenger fatality in the United States in over 90 million flights.”

Facing a crisis

The job of Boeing’s board got more challenging in October 2018, when a 737 Max crashed into the sea off the coast of Indonesia. With 189 deaths, it was the deadliest accident in the 50-year history of the Boeing 737, according to the Aviation Safety Network. Half of the directors who approved the jet were still on Boeing’s board, but the boardroom was now led by Muilenburg.

Soon after the crash, Muilenburg briefed the board on the process that would unfold next, Calhoun said. Boeing would work with investigators to try to determine the cause of the crash, while its engineers would discuss whether any safety improvements to the 737 Max were warranted.

“Everybody holds their breath,” Calhoun said. “You hold your breath and you begin to think about all the responsibilities you now have.”

For Calhoun, one responsibility was learning for the first time about the MCAS. Boeing intended the software to automatically adjust the plane so that it behaved like earlier models of the 737. But preliminary reports on the Indonesia crash showed pilots of the Lion Air plane struggled to deactivate it in the seconds before they crashed.

Calhoun’s review concluded that the MCAS itself was working as intended, and had met the company’s criteria for safety when it was built. “The engineering disciplines that were deployed in the development and the implementation of the MCAS were sound and well-executed,” Calhoun said.

Meanwhile, Boeing was taking steps to buttress its investor relations. The board of directors approved a plan to give $20 billion in cash back to investors in the form of stock repurchases — the largest buyback program in company history — and raise the dividend, or amount it pays out to every investor every quarter, by 20 percent.

The decision to ground

On March 10, another crash of a 737 Max jet in Ethiopia plunged the company into crisis. Regulators all over the world ordered a grounding of the jet, based on preliminary findings that the plane showed a similar flight path to the Indonesian plane.

Boeing initially tried to reassure the public of the plane’s safety. In a conversation with Trump on March 12, Muilenburg urged the president to keep the 737 Max in the sky, according to an administration official with knowledge of the discussion. The FAA became one of the last regulatory holdouts, saying a review of the plane found no reason to take it out of the air.

But the next morning, Calhoun says the board had a phone call to review new evidence from “a Canadian source” that showed the MCAS had likely been activated. Based on that, they decided to recommend to regulators and airlines that the 737 Max be grounded, he said.

Muilenburg called Trump a second time to advise the grounding, Calhoun said. According to an administration official, Muilenburg said he wanted to work with the White House to coordinate an announcement about the grounding. But soon after the call, Trump publicly announced the grounding before Boeing could issue a statement. That was followed by an official order from the FAA.

A White House spokesman did not respond to requests for comment.

The same week, Boeing’s board released its annual report on the company, known as the proxy. A proxy usually tells investors how the board assessed the performance of the CEO, how they calculated the pay of top executives and whether any new risks to the company have become apparent. Boeing’s proxy made no mention of the 737 Max or how its grounding could affect the business. Boeing’s spokesman said the document was completed and printed March 8 — two days before the Ethiopia crash — but was filed to the Securities and Exchange Commission after the crash, on March 15.

The board approved a pay package for Muilenburg of $23.4 million — a 27 percent raise from the prior year — arguing in the proxy that “2018 was a very strong year for Boeing,” including record revenue, profit and airplane deliveries. But in April of this year, with sales of all 737 Max planes on hiatus, the company took the unusual step of withdrawing its financial outlook for the year and said it would temporarily halt the stock buyback program.

The Department of Transportation last month formed a special committee to “determine if improvements can be made to the FAA aircraft certification process,” after members of Congress criticized the aviation agency for delegating too many aspects of plane certification to Boeing. Separately, Boeing said four of its board members formed a new committee to “confirm the effectiveness of our policies and processes for assuring the highest level of safety on the 737 Max program” as well as other airplanes.

A trusted leader

On a rainy Monday morning late last month, Boeing’s board members shared a bus ride from a Chicago hotel to the annual shareholder meeting at the city’s Field Museum. As their bus pulled into the museum parking lot, they passed a group of five men standing in the rain, holding umbrellas and poster boards with the faces of victims from the two 737 Max crashes. The directors were chased by reporters as they were ushered inside to their seats at the front row of the auditorium.

Later that day, the board held a meeting focused exclusively on how Boeing is responding to the crashes, Calhoun said. After discussing recent news about regulator approvals for Boeing’s 737 Max software update and the latest details being learned from the crash investigations, Muilenburg left the room to give directors a chance to discuss any concerns about his leadership.

The “executive session” — a tradition at all Boeing board meetings — was brief.

“Dennis has our complete and total confidence,” Calhoun said. “We feel very strongly that he is doing the right things.”

Josh Dawsey contributed to this report.