Fuente: The Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance and Financial Regulation

Autor: Bhakti Mirchandani, Allen He, and Victoria Tellez, FCLTGlobal.

Through our research, FCLTGlobal aims to identify the key determinants of long-term success for companies and investors around the world. We then use this knowledge to encourage long-term behaviors across capital markets. This post focuses on predictors of long-term health that are grounded in rich global data going back over time. Looking across the value chain—at companies, asset managers, and asset owners—we find the following:

- Global companies are falling short on long-term behaviors. Companies are scoring lower than they did in 2014, and well below the level reached before the financial crisis, on our overall measure of long-term behavior.

- Overdistribution of capital can be a drain on corporate performance. Although distributing capital via buybacks and dividends makes sense in some circumstances, our analysis finds that companies taking this approach tend to generate lower five-year returns on invested capital (ROIC, our preferred measure of performance).

- Corporate research and development (R&D) can boost returns. By looking at the marginal value of additional research spending, we show that R&D investments are linked to higher ROIC.

- Employee ownership is linked to higher returns among global asset managers. Employee ownership is the strongest predictor of success for asset managers, particularly those in equity investing.

- Net returns for asset owners are linked to both governance and investment strategy. Relevant factors include board diversity, active ownership, lower costs, a higher funded ratio, and higher exposure to both public and private equity. Of course, not all drivers of long-term success are easily measured or detected, and if more data were available, we could deepen our understanding of vital factors such as talent retention and customer loyalty. But even with existing data limitations, we are able to confirm some well-known predictors of long-term success and also unearth some novel ones. What follows is a fuller account of our findings, our methodology, and our thoughts on how best to extend these results in the future.

Factors Associated with Long-term Performance of Corporations

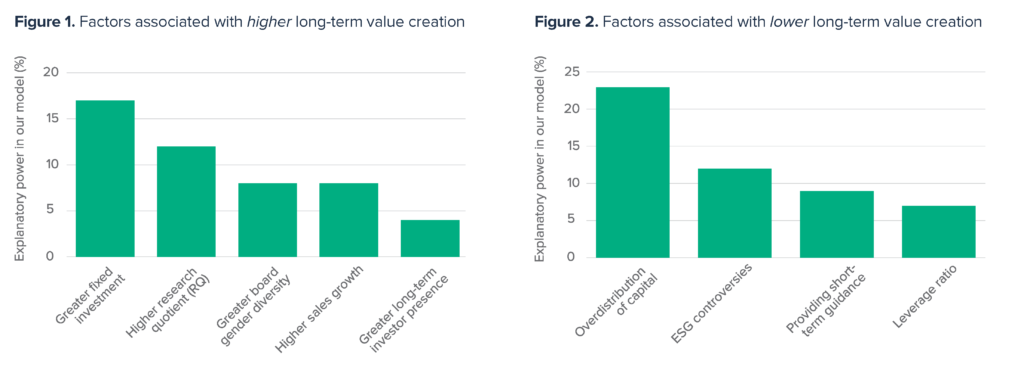

Our analysis identified a range of factors associated with the long-term health of companies, which we split into two buckets: positively correlated factors that predict long-term health and negatively correlated factors that suggest weakness ahead.

The factor most strongly bound to long-term performance was actually one of those negative factors—something to avoid—namely, overdistribution of capital in the form of dividends and buybacks that exceed the free cash flow generated by the company. Naturally, efforts to return money to shareholders can and do make sense when companies do not have more attractive investments to pursue. And it is possible that the causal link actually runs in the other direction—that is, companies with limited growth potential may be more likely to return money to shareholders. But our analysis shows that capital distributions to investors in excess of free cash flow are associated with weaker ROIC.

Another factor that weighs on long-term value creation is excessive leverage—though, again, this is not a blanket dismissal, as leverage can be vital to businesses and borrowing can be an auspicious sign that a company has ideas worth pursuing. As a general tendency, though, more leverage among companies in our dataset translates into lower ROIC.

Factors Associated with Long-term Performance of Asset Managers

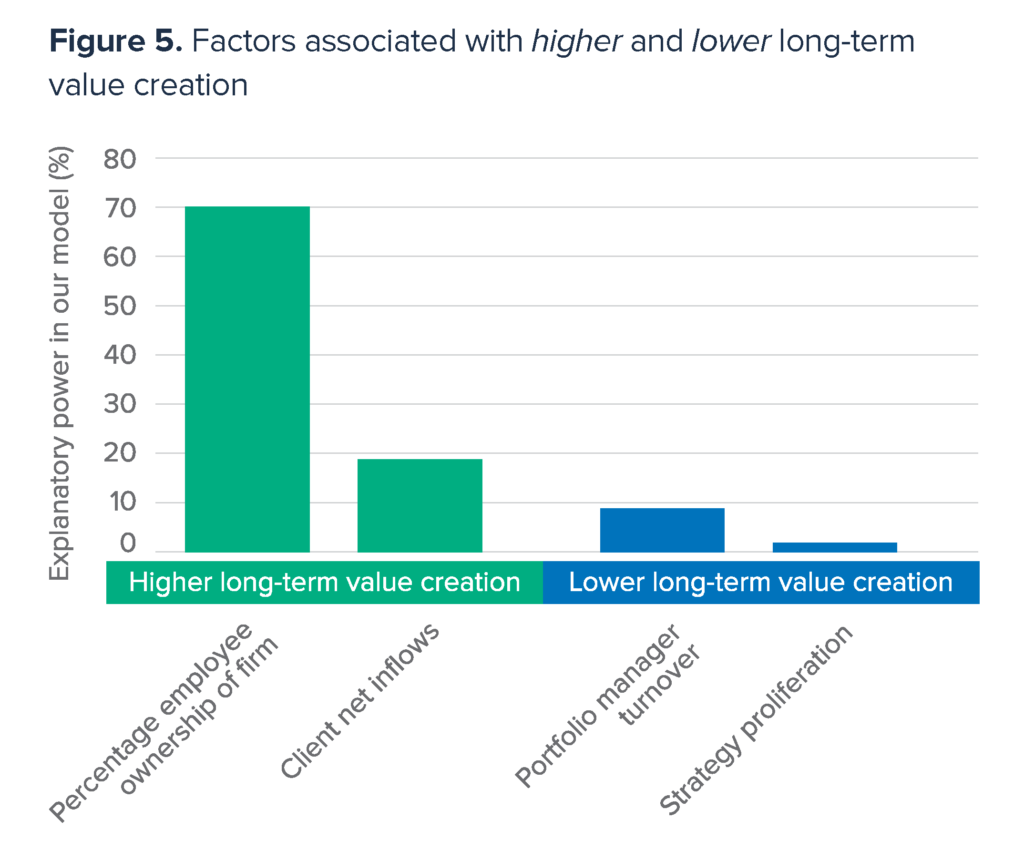

Asset managers with the strongest long-term gross returns tend to have a high level of employee ownership, which may help to align incentives. Having high net inflows is also a positive indicator, though this finding may reflect the ability of successful managers to attract money—rather than any tendency for growth to improve returns.

On the flip side, turnover among portfolio managers is an indicator of trouble ahead as is strategy proliferation.

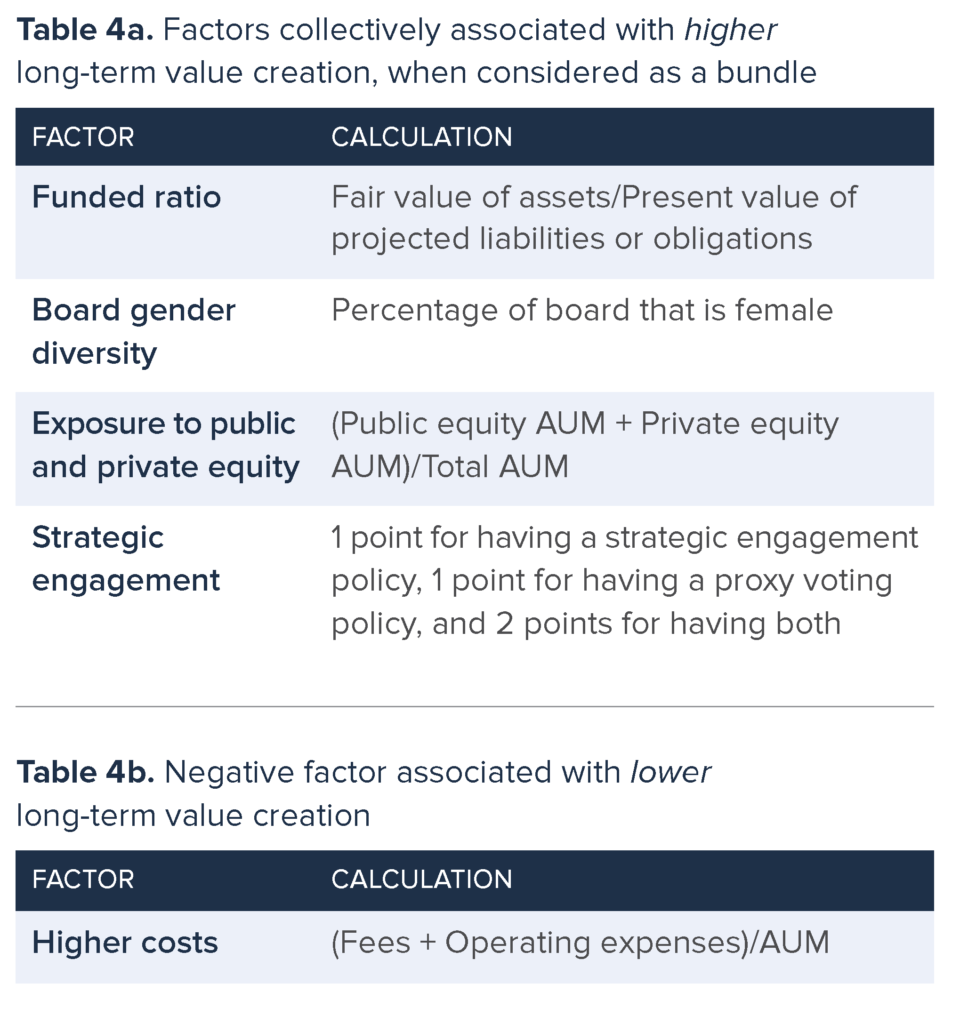

Factors Associated with Long-term Performance of Asset Owners

Given the data limitations, the only discrete factor that we were able to definitively associate with long-term success is the percentage of a portfolio allocated to equities—where higher equity allocation is a statistically significant predictor of long-term value creation. Although we recognize that this finding may reflect the rising equity markets during the 2012-17 time frame that we are considering, it is consistent with research on how the risk premium affects equity returns over time. Pooling factors suggests that net returns may be connected to a suite of strategies and behaviors that include gender diversity on the board, strategic engagement, lower costs, a higher funded ratio, and higher exposure to both public and private equity.

Conclusion: More Data Means Richer Knowledge

The depth and breadth of our findings is limited by the availability of high-quality and complete global datasets. To counter these limitations, we followed a rigorous process beginning with a thorough literature review of academic and investment research to identify factors supported by existing studies. We then decided to focus on factors with rich, global data (and no more than 20 percent missing data), allowing us to measure granular change year over year. After consulting with a broad range of experts, we moved to the data analysis phase, using more than 20 million data points to distill which of the pre-vetted factors had a statistically significant impact on long-term value creation.

While we are proud of the rigor of this approach, no method is perfect. Our focus on factors with broad data prevented us from evaluating aspects of talent and culture that we know are vital to the long-term prospects of corporations, asset managers, and asset owners. These include customer satisfaction and employee engagement, both of which have been shown to be connected to long-term success.

Similarly, although our minimum 80 percent data completeness standard limited some of the biases associated with missing data, it also eliminated whole dimensions of information from our purview, such as executive compensation duration—which has been linked to long-term performance in academic work but where global data is currently incomplete. Such incomplete data create space for omitted variable issues, distorting our ability to measure the true explanatory power of the factors that we can regress (omitted variable issues plague a wide range of attempts to describe complex multidimensional issues with academic rigor). But even with imperfect data, we were able to advance the state of knowledge around long-term behaviors by isolating and identifying a number of the key factors correlated with long-term success around the world and across the value chain. In the corporate world, that includes appropriate reinvestments in the business rather than overdistributions of capital, productive R&D, and an end to quarterly guidance—to name just a few. For asset managers, it means embracing employee ownership as a paramount concern (on the equity side). And among asset owners, it means embracing the reality of the equity risk premium, among other things.

The next step—for FCLTGlobal in particular and the spread of long-term thinking in general—is to amass a richer universe of data and a broader array of methodologies to drive the research forward. We are working with our members and other business, academic, and policy leaders to accomplish just that while pursuing a more integrated approach to understanding the deepest drivers of long-term success, whether they have to do with governance, incentives, engagement, strategy, or public policy.

The complete publication is available here.