Fuente: The Wall Street Journal

Autor: Vanessa Fuhrmans

Well before the glass ceiling, women run into obstacles to advancement. Evening the odds early in their careers would have a huge impact.

The conventional narrative of the ambitious woman at work goes something like this: Woman joins the workforce with big dreams. Over the years, she advances in her career alongside male colleagues. Yet on the way to the top, she hits an invisible barrier to the highest corridors of power.

Long before bumping into any glass ceiling, many women run into obstacles trying to grasp the very first rung of the management ladder—and not because they are pausing their careers to raise children—a new, five-year landmark study shows. As a result, it’s early in many women’s careers, not later, when they fall dramatically behind men in promotions, blowing open a gender gap that then widens every step up the chain.

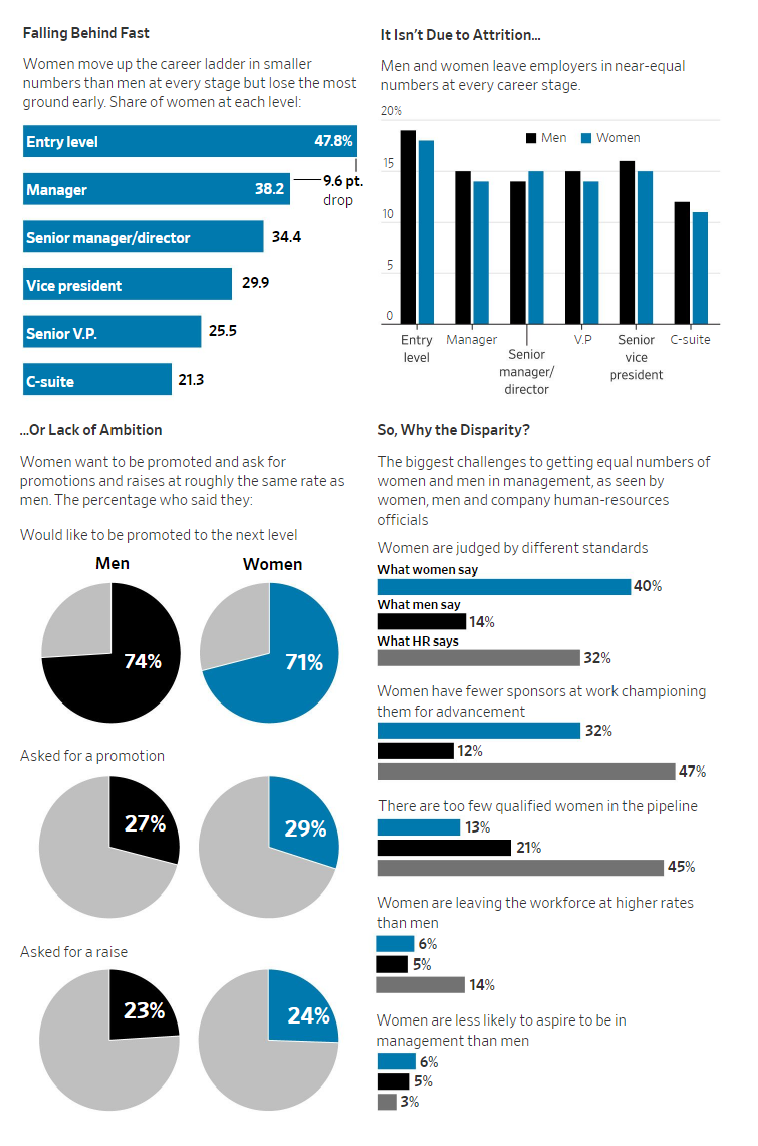

The numbers tell a stark story: Though women and men enter the workforce in roughly equal numbers, men outnumber women nearly 2 to 1 when they reach that first step up—the manager jobs that are the bridge to more senior leadership roles. In real numbers, that will translate to more than one million women across the U.S. corporate landscape getting left behind at the entry level over the next five years as their male peers move on and upward, perpetuating a shortage of women in leadership positions.

Few efforts are likely to remedy the problem as much as tackling the gender imbalance in initial promotions into management, says Lareina Yee, a senior partner at McKinsey & Co., which co-led the research with LeanIn.Org. If companies in the U.S. continue to make the same, tiny gains in the numbers of women they promote and hire into management every year, it will be another 30 years before the gap between first-level male and female managers closes, McKinsey estimates. But fix that broken bottom rung of the corporate ladder, and companies could reach near-parity all the way up to their top leadership roles within a generation.

Earlier than believed

Those are some of the key findings of the fifth annual Women in the Workplace study conducted by Lean In and McKinsey, one of the most comprehensive examinations to date of the experiences of working women and men. Data from 329 companies with a collective 13 million people on their payrolls (including Dow Jones & Co., publisher of The Wall Street Journal) suggest the barriers holding women back from equal power and influence in the workplace emerge much earlier than many corporate leaders believe.

“Bias still gets in the way—bias of who you know, who’s like you, or who performs and operates the same way you perform and operate, whose style is more similar,” says Carolyn Tastad, group president of Procter & Gamble’s North American operations. But “we have to find ways to pull all this talent up through the pipeline.” She adds: “The even bigger question is: What can it do for our business?”

A growing body of research links greater gender diversity on teams and in corporate management to more innovation and better financial performance. That business case is a big reason more senior leaders at companies—73%—say achieving equality for women in the workplace is a priority, up from 56% four years ago.

Yet fewer than a fifth of employers surveyed attributed the gender gap in their own management ranks to women losing the first-time promotion race, the data show. This is even though for every 100 men promoted or hired into junior management roles, only 72 women are, a ratio that has barely budged from 2015. The percentage of black and Hispanic women getting that initial shot at leading others is even lower.

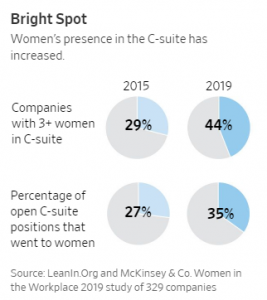

Employers’ moves to diversify their most senior echelons could provide a road map, says Rachel Thomas, president of Lean In, the nonprofit founded by Facebook Inc. ’s Sheryl Sandberg to support women in their career ambitions. Over the five years of the study, women have made the biggest gains at the very top of the corporate ladder in the C-suite, as companies have trained their sights on grooming a select cadre of high-potential senior-level women for the biggest jobs in management. Nearly half of companies have at least three women in their top leadership teams, up from 29% in 2015. Overall, the share of women in the C-suite has climbed to 21% from 17% five years ago.

“We’ve seen that if companies really put their minds to it, they can bring about change that matters,” Ms. Thomas says. “If they can apply the same extra elbow grease that they do at the top to the broken rung, I’m bullish they can fix it.”

The problem starts early

Some companies, such as BioMarin Pharmaceutical Inc., are giving executive-level coaching to junior would-be leaders in the hopes of promoting them. The 3,000-person biotech firm in San Rafael, Calif., launched a pilot with Pluma, a web and mobile platform that provides video-session coaching, with 51 participants, 28 of them women. Since then, 35% of the women and 14% of the men have moved up into new jobs.

One of them, Lillian Lee, landed a role as associate director in clinical operations, guiding a team of nearly 20 people that runs clinical trials of drugs, a big jump from her previous role overseeing a few direct reports. Her regular coaching sessions helped her realize getting ahead didn’t require “just putting your head down and doing the work,” she says. “If you want to be known for your work, relationships are fundamental.”

No lack of ambition

The numbers show that the first step is the steepest for women. But why is that? What’s holding women back from climbing that first rung into management?

What women’s work looks like now

Women make up about half of the U.S. workforce today, but many jobs remain largely segregated along gender lines. Explore the fields in which women have made the most inroads, and the least.

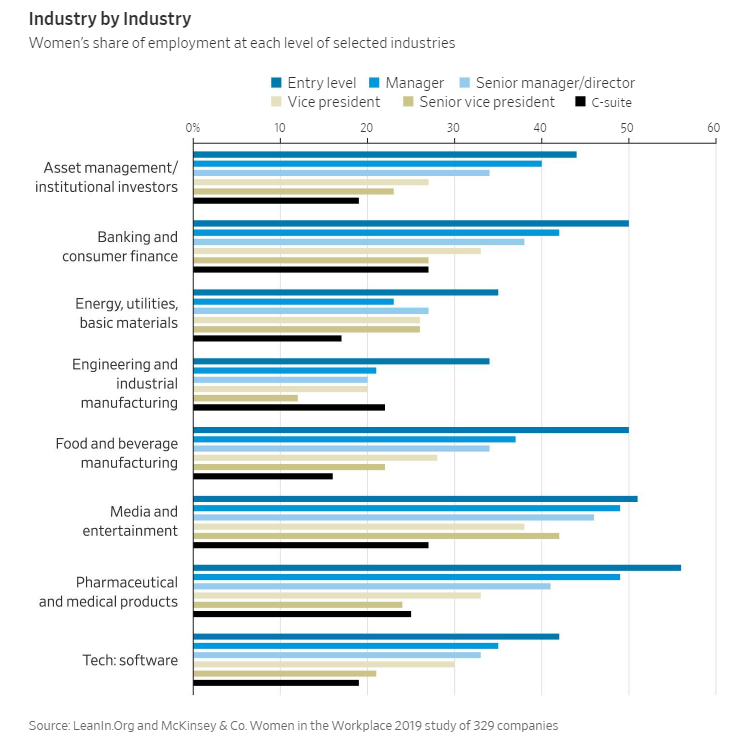

The upshot: At nearly every career stage, the disparities between men and women have narrowed only marginally since the Women in the Workplace research began in 2015. Even in industries with largely female entry-level workforces, such as retail and health care, men come to dominate the management ranks—a phenomenon that Haig Nalbantian, a labor economist and co-leader of consulting firm Mercer LLC’s Workforce Sciences Institute, calls “the flip.” Mercer is a unit of Marsh & McLennan.

To help companies understand where and why they are losing women along the chain, Mr. Nalbantian deploys predictive analytics to create elaborate flow charts of the number of men and women promoted, hired and leaving their jobs at every level of the organization. Some employers, he says, are in industries dominated by men top to bottom. The pattern he sees more often, though, is sizable numbers of women occupying jobs at the bottom of the pyramid—but at the junior and midlevel management levels, men suddenly pull sharply ahead. From there to the top, men increasingly outnumber women.

“In all my years of doing this, and I have done this for hundreds of companies, I have yet to see an organization that doesn’t have a flip,” he says of the companies in which women make up a fair share of the entry-level workforce.

“In all my years of doing this, and I have done this for hundreds of companies, I have yet to see an organization that doesn’t have a flip,” he says of the companies in which women make up a fair share of the entry-level workforce.

One factor, he says, is that even in many “female-friendly” sectors, entry-level women still tend to get hired into jobs with limited upward mobility, such as bank tellers or customer-service staff. In more professional-level roles, women also are less likely to be in jobs that can accelerate careers, such as dealing with high-profile clients or helping build a line of business. More often, they take on or are steered into support roles, such as project management.

The hot jobs

Even among men and women identified as having high potential from the start, women are less likely to get the “hot jobs” that are springboards to bigger roles. In a 2012 study of more than 1,600 M.B.A. graduates by the research and advocacy group Catalyst, men reported leading projects with larger teams and budgets twice the size of women’s. Their work was also more likely to be on the radar of the C-suite.

“When companies ask, ‘What’s the one thing we can do systemically?’ we say, ‘It’s not quotas, it’s not targets,’” says Mr. Nalbantian. “It’s about how do you position women and minorities to succeed in the roles that are likely to lead to higher-level positions.”

Over time, many women come to see a workplace stacked against them. Among the more than 68,500 employees whom McKinsey and Lean In also surveyed from the participating companies, a quarter of women said their gender had played a role in a missed promotion or raise. Even more expected it to make it harder for them to get ahead in the future.

The takeaway for some women is that they have to assemble their own career ladder. After working for more than a year in sales at an Atlanta-based financial-services company, Rebecca Weizenecker wanted to vie for a job heading a direct-sales team. Before applying, she went to the hiring manager and asked him to be candid about her strengths and weaknesses. At 24, she lacked experience, he said. She pressed for specifics.

“‘What are the specific gaps, and are we talking 10 years of experience or is this a three-month learning curve?” she says she asked. When he told her it was probably a matter of months rather than years, Ms. Weizenecker put together a 90-day plan that included additional training. Soon after, she landed the job.

“I made it hard for them to say no,” says Ms. Weizenecker, now 29 and vice president of sales and marketing at FundThrough, another financial-technology firm.

Making the call

At Synchrony Financial, where 46% of all managers are women, CEO Margaret Keane says she wanted to build a sturdier bridge from the entry-level jobs in the consumer bank and credit-card issuer’s call centers to the managerial track. Many of those jobs are held by women. “I feel I have as a woman CEO a responsibility in terms of driving the culture,” says Ms. Keane, who began her own career in a bank call center.

One way is a nine-month development program that allows call-center and administrative staff to hone their management skills, such as leading meetings and giving high-ranking executives their elevator pitches, while exploring different career paths across the company. Of the several hundred employees who have completed the program since it began in 2013, more than 250 have been promoted to managerial positions, 60% of them women.

One is 29-year-old TJ Wright, a bank representative who jumped to become an assistant vice president in Synchrony’s consumer-banking operations in Charlotte, N.C., in January. Key to landing it, she says, were a couple of senior executives who sponsored her, championing her for bigger roles. Unlike mentors, who largely offer informal guidance, sponsors open doors to other powerful contacts and advocate for their protégés when big projects or promotions come up—something the McKinsey and Lean In data show is instrumental in propelling the careers of both men and women.

“When I got my new job, I was so excited to tell my sponsors,” Ms. Wright says. “They said, ‘We know, we were in the room having those conversations about you!’ ” Nearly a year into her new role, she has mapped out her next couple of potential moves and hopes to land a promotion to vice president next. “I’ve got to pace myself a little bit,” she says.

The sponsor’s role

At Bank of America, where more than 40% of people in management are women, sponsorships play a critical role in helping women advance, says Cynthia Bowman, head of diversity and inclusion and talent acquisition at the bank. To secure a sponsor, “you’ve got to consistently perform, have a strong brand and deliver. That’s just table stakes,” she says. “But a lot of people do that and might still not move, because they don’t have the right support.”

Up-and-coming women have the chance to be matched to senior players in several ways. Over the past three years, more than 4,100 women have participated in one of the company’s formal career-development programs, through which many get sponsors. The bank estimates many more women have found sponsors through other programs within its various lines of business and regular forums it organizes for them to get facetime with high-level executives.

To measure how its efforts are working, Bank of America tracks its workforce data meticulously. At least once a month, senior leaders receive updated scorecards tracking the representation of women at every level. Lower-level managers are also expected to meet certain goals, such as interviewing a diverse slate of candidates for open positions.

Procter & Gamble also takes a granular approach to evening the gender playing field. Women hold 47% of all management roles at P&G, up from 44% four years ago. The consumer-goods giant applies the same rigorous approach that it uses for market research to help employees map their career-development plans. When the company spotted a drop in the share of midlevel female managers, it started tracking their progression earlier and more closely.

“Today we can pull that data, slice it by function, by geography. We can spot weaknesses quickly and whether they might lead to a pipeline deficit,” says Deanna Bass, P&G’s director of global diversity and inclusion.

The individual career plans identify what sorts of experience employees need and are acquiring, and the likely next promotions they have the potential to attain. If someone has been in a job longer than initially mapped, “it allows us to go back to her manager and say, ‘She’s been here several years and hasn’t moved. Can she be promoted?’ ” she says. “The role of the manager is critical to their success.”

Luz Damaris Rosario, who began working as a chemist at Goya Foods when she was 22 and now oversees one of the company’s largest food-production plants, in Houston, credits an early promotion with catapulting her career. Within two years of joining the company, she was made a laboratory manager, overseeing a team of scientists in a Puerto Rico plant producing canned beans and tomato sauce.

“That promotion empowered me,” she says, adding that it gave her greater access to senior Goya executives and a broader understanding of how the company operates. “It was, ‘The world belongs to me,’ ” she says.

One of those senior leaders, the president of Goya’s Puerto Rico operations at the time, helped pay for her to get an M.B.A. after she told him she hoped to head one of the company’s operations one day. Now, at 56 and with many more promotions under her belt, Ms. Rosario says she advises younger women to stay alert to new roles and look for ways to grow.

“Don’t think you’re competing with your male counterparts,” she says. “Just compete with yourself.”