Autor: Dina Medland

There is no evidence today that trust in financial services is higher in 2020 than it was in 2010, after the financial crisis that we are still talking about. Trust has been a shrinking commodity all over the world over the last decade and more – in politics, in business, and in the media. The climate crisis in which we all find ourselves is a chance for the financial sector to play a critical part in putting that right.

A report funded by eight banks from around the world and just published by the Banking Environment Initiative (BEI) and the University of Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership (CISL) looks at ways in which banks can serve to accelerate the financing of the low carbon economy, and in so doing develop a vision for a bank of 2030. Long-term success, it says, is “associated with the ability to help clients secure capital at a rate that makes a low-carbon investment more atttractive and connect clients with experts to develop a compelling low-carbon investment case and provide ongoing assistance with its implementation.”

In interviews with senior bankers in Europe, Asia and the Americas the project found that, despite the new challenges being thrown up by the climate crisis, many remained in their comfort zones working on a banking-as-usual basis. Others, however, are adopting “pioneering behaviour” supporting clients in the transition to low carbon. It’s a good example of leadership along the lines of a model of the stakeholder governance we increasingly need in the UK today.

The world has moved swiftly from talking about a ‘climate crisis’ alongside the need for ‘sustainability’ to referring to a ‘climate emergency.’ Sustainable business models rely on the ability to transition. It is estimated and well documented that without deep and sustained cuts to greenhouse gas emissions, we are on course for a 2degree C increase around 2050. “This could mean an increase in the global population facing water scarcity of nearly 400 million, and the cost of annual flood damage losses from rising sea levels of more than $11tn” says the report. The cost of doing nothing cannot be quantified, or imagined.

Or, as Henri de Castries, the then-CEO and chairman of AXA, one of the world’s largest insurers, said in 2015 and I reported : “A 2 degree C world might be insurable. A 4 degree C world certainly would not be.”

So how are banks reacting ? Some banks, according to the report, are taking a strategic approach to the low carbon economy that “unlocks latent demand for green investment by clients.” Importantly, such initiatives are independent of regulatory or policy support, and channel capital into the low-carbon economy in a variety of ways.

They include taking direct risk exposure with clients with green bonds, structuring via the capital markets (transition bonds), increasing their own lending capacity via green securitisation and innovations in funding such as ring-fenced venture capital funds. The report offers further details.

When a business does well in fast-changing times, it is often because its leadership recognises the essential steps needed to generate future revenues. It is more likely to do that if it is well-connected to thinking among its stakeholders. Not only is a younger global generation mobliising behind climate action, but there is far more awareness among regulators and policy makers that best corporate governance demands action with a long-term perspective mindful of the imprint a business leaves on society. That younger generation is also the future customer base and the momentum of public awareness and demand around a climate emergency is growing.

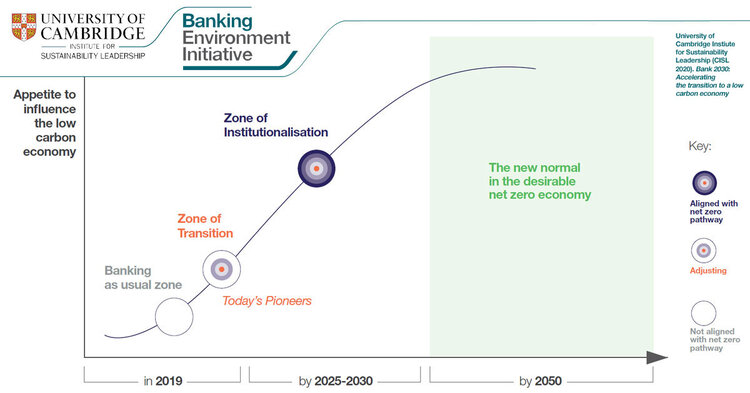

The report sets out the argument that banks need to evolve rapidly towards financing that “makes the future possible”, rather than merely serving the market as they have always seen it. They need to move along the curve towards ‘“the new normal in the desirable net zero economy.”

Figure 1. Bank 2030: Accelerating the transition to a low-carbon economy; Source: Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership, University of Cambridge January 30, 2020.

The banks funding this report include BNP Paribas, Deutsche Bank, LBBW, Lloyds Banking Group, Morgan Stanley, Santander, Standard Chartered and Wells Fargo. CEOs of leading banks were behind the creation of the BEI back in 2010, with a mission to lead the banking industry into collectively directing capital towards environmentally and socially sustainable economic development. More recently, Mark Carney, the governor of the Bank of England, has repeatedly warned of the consequences for business of ignoring climate reality.

As the voices around the need for a low carbon transition get louder, this report looks at the multiple ways in which banks can evolve the product offer and move towards greater collaborative finance including direct support for early stage innovations. and the facilitation of crowd funding to make smaller projects possible. They can expand their coverage by looking at the range of customer needs, from encouraging the transition of agricultural practices, to helping “harder to abate” sectors such as cement or shipping be part of a low-carbon transition.

“By the end of this journey, the new business lines created by ‘leaning in’ to channel more capital to the low-carbon economy have taken over the bank. It will have transformed its business and operating model” says the report.

It lays out the opportunities of growing the low carbon pipeline and deriving commercial benefit for doing so, with the Industrial Bank of China (IBC) as an example. IBC differentiated itself in its expansion efforts by positioning itself in the green finance market in 2005. A small regional player at the start, by 2016 it had become the seventh largest bank in China by total assets.

The cost of inaction is also explored by the report – with due note to pressure from investors, employees and civil society – and there is a section on legal liability. Banks have already moved away from thinking about climate change as a reputational risk issue to a strategic concern. Now they need to follow through by adjusting their business and operating models.

By embracing a shared vision, banks can become the intermediaries for capital and expertise to flow to clients who buy into and align with a low carbon future, it suggests.

Banking has struggled with issues of trust since the last financial crisis even while it continued to pay large fines on its transgressions. Existing business models are floundering and as traditional revenue lines are squeezed, many businesses find themselves struggling with re-invention, and job cuts. Place the climate emergency as the real-time backdrop image, and the report’s findings make sense of a way to bring employees, products and clients together, for best stakeholder governance – and profitable wellbeing.

Businesses looking at how to do things differently, to do them better in pursuit of common goals are now what is capturing the public’s imagination. “The environmental and social challenges we face are interconnected. This means that, although our research concentrated on climate change imitigation, the roadmap to a low carbon bank of 2030 developed by this project could represent a preliminary sketch for a bank capable of tackling the wider SDGs” says the report.

Just imagine that – if bankers came to be thought of as the ‘good guys’, that certainly would be welcome reinvention.

Note: The full report can be downloaded from the CISL website: www.cisl.cam.ac.uk/publications