Fuente: PwC en The Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance

Autor: Paula Loop, Paul DeNicola, and Leah Malone, PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP

PARA VER EL DOCUMENTO COMPLETO, HAZ CLICK AQUÍ

Introduction

2020 has presented unprecedented challenges for companies. While the year generally started like any other, by the end of the first quarter, the COVID-19 pandemic created an unprecedented global health emergency. Business was upturned across the globe, unemployment shot through the roof, US GDP took the greatest fall on record, and many workforces shifted to an entirely remote setting, all while communities confronted untold sickness and fatalities. America also saw a new level of social unrest, as protests for racial justice swept the nation. Against all of this, a presidential election looms.

With everyday life upended, boardrooms changed drastically. Gone were the site visits, strategy retreats, and board dinners. Gone was the boardroom itself. But the work didn’t slow, and most directors reported devoting significantly more time to their duties.

In many ways, directors believe that boards and companies have met the early challenge, even during the crisis. Boards show increased awareness and increased focus on areas that institutional shareholders have emphasized in recent years, like environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues and shareholder engagement. They have made changes to deal with problems in company culture, and they are thinking more broadly about issues like company strategy and executive compensation. In many ways, they are responding to the current climate and to shareholder concerns. But in other ways, boards continue to be plagued by seemingly intractable problems. Directors continue to report dissatisfaction with the performance of some of their peers. Board refreshment still lags as leadership frequently avoids both the tough conversations with directors who should be replaced and the hard work of long-term board succession planning. Boardroom discussions suffer as directors, keen to maintain a collegial atmosphere, avoid sharing dissenting views. And even while making some improvements in boardroom diversity, directors aren’t always convinced of the importance of that diversity.

Boards face all of these challenges against the backdrop of a global crisis. But while the challenges are significant, this moment of crisis also creates opportunities. Forward-thinking boards find ways to inspire positive change. With strong leadership, boards may be able to leverage the crisis into changes in board composition, revamped board practices, re-envisioned diversity and inclusion efforts, and re-focused board priorities.

Risk and strategy

Director blind spots pre-crisis

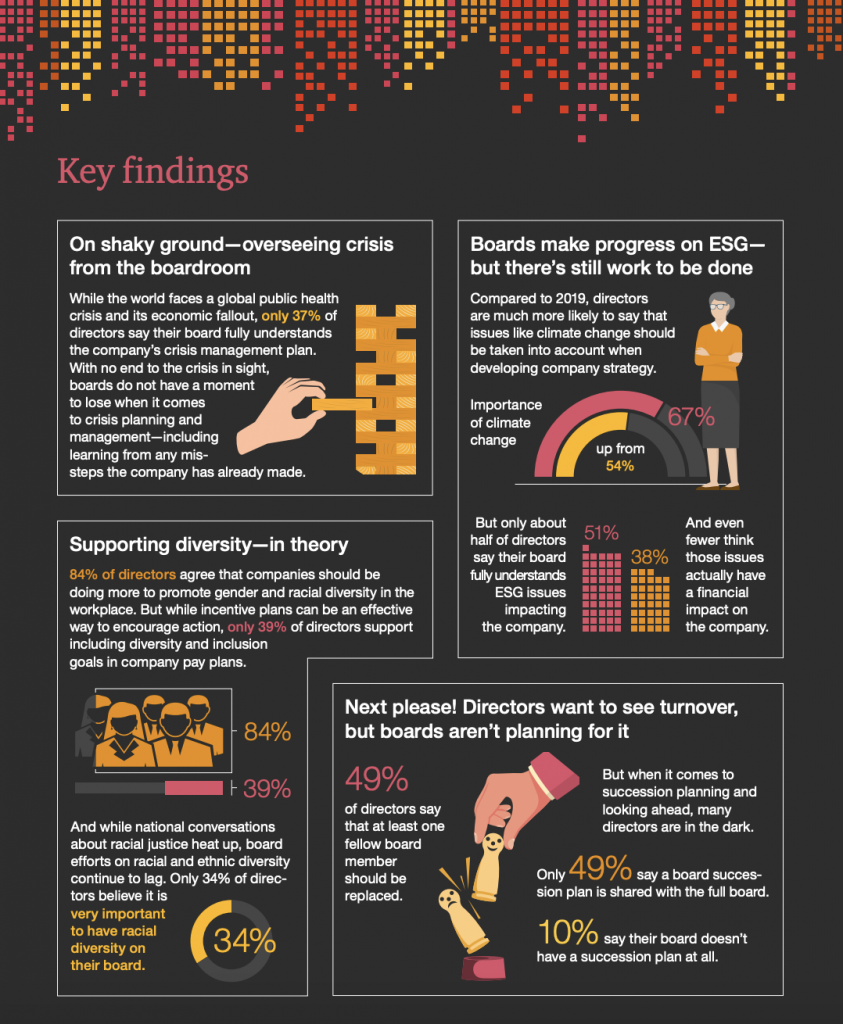

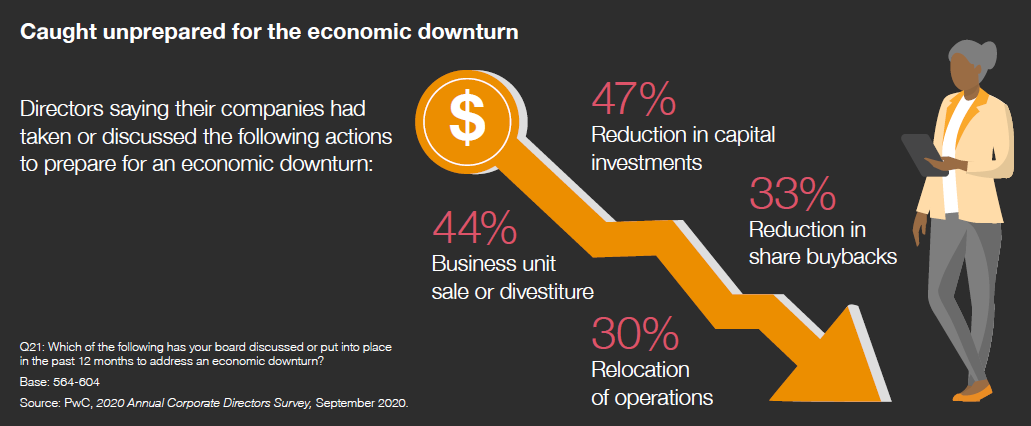

Although the COVID-19 pandemic took most of the world by surprise, signals of a potential economic downturn had been emerging for months. Yet many directors say their boards had not taken steps to prepare for a downturn in the 12 months before the recession began.

More than a quarter of directors (28%) said their companies had not taken any steps at all to address a downturn. Fewer than half of directors (47%) say their boards had reduced capital expenditures. Forty-four percent (44%) had explored a sale or divestiture, but only one-third (33%) had reduced share buybacks, which would increase cash reserves or liquidity. In the year prior to the recession, only 14% had reduced the share dividends that investors had come to expect.

While many companies were caught off guard by the downturn, boards can take this moment to address central issues of strategy and capital allocation. Half of directors (50%) report that since the COVID-19 pandemic, their companies have reorganized debt structures and/or made changes to their capital allocation. Few say they have increased their M&A activity, as many companies find ways to shore up capital for now. But finding the right uses for that capital as time goes on will rely on boards’ ability to take a long-term view on the future of the company.

Crisis management demands more attention

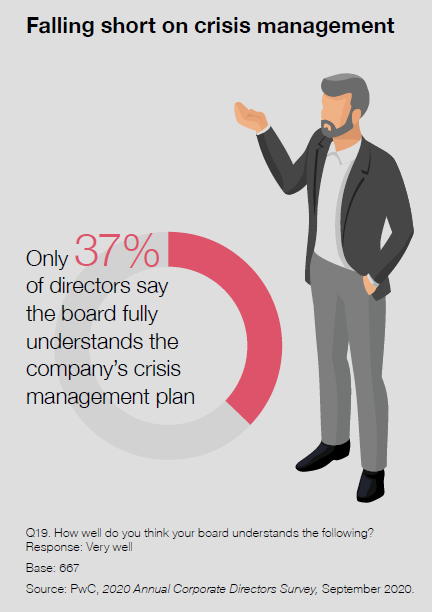

The COVID-19 pandemic showed all companies how quickly a crisis can grow, and how easily the unprepared can fall. While the scope of the pandemic caught most of the world by surprise, companies need to be prepared to face unexpected circumstances, and having a response plan in place is key.

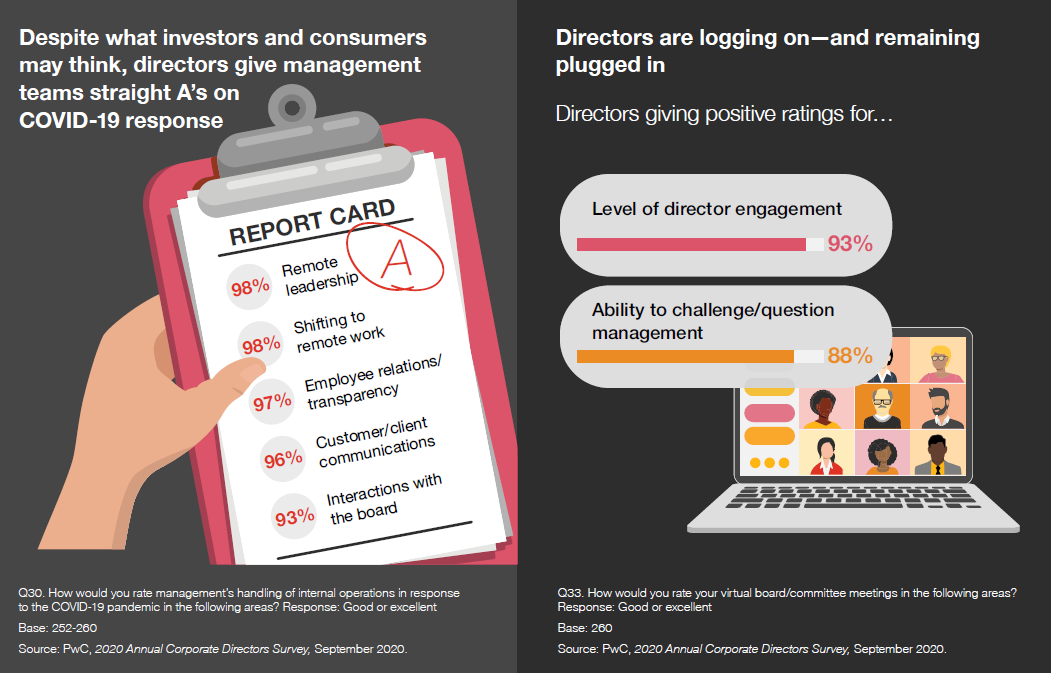

Surprisingly, only 37% of directors say that their board has a strong understanding of the company’s crisis management plan. But despite not fully understanding the plan, and despite the clear missteps many companies made, most directors gave management high marks for their performance during the crisis. Ninety-nine percent (99%) of directors said companies did a good or excellent job of dealing with interruptions in internal operations due to COVID-19. Ninety-six percent (96%) said the same for management teams dealing with supply chain interruptions— even though consumers are likely to have a different take.

Even if these companies navigated the first part of the COVID-19 challenge successfully, it doesn’t necessarily follow that they will have success with the next crisis. A crisis plan will grow stale unless it is revisited after the event and revised in light of what worked and what didn’t. As part of that process, boards can push their management teams to find opportunities within the crisis. Those that are able to do so will come out on top.

PwC perspective

In crisis preparedness, don’t overlook the value of looking back

Any company can be hit with a crisis at any time, from a cyber breach, to a safety issue, to an environmental disaster. But rarely are so many companies confronted with a crisis at once. 2020’s COVID-19 pandemic and its associated impacts gave almost every company a taste of crisis management. And while that crisis and its economic impact is certainly not over, companies can benefit now from launching a comprehensive crisis review.

While most directors were pleased with their management team’s response, there were clearly winners and losers in the early part of the crisis. Boards can leverage their companies’ experiences so far in 2020 to spur a complete evaluation of what worked, what didn’t, and what needs to improve in the future. Through that evaluation and revision exercise, directors may also benefit from a deeper understanding of the whats and whys of the crisis plan. They will also be more prepared for the next chapter. For more on crisis management, read Being prepared for the next crisis: The board’s role.

Spotlight: COVID-19 resources for the board

The COVID-19 pandemic and its fallout are testing companies like never before. Most directors say executives have done a great job of navigating the challenges thrown at them in the early days of the crisis. They praise their own boards as well, reporting high levels of director engagement and a strong ability to challenge management.

Directors show confidence today, but of course not all companies managed 2020’s challenges well. Some companies faltered, or even failed. For those that made it through, the crisis is far from over, and key challenges remain ahead. While confidence can be a good thing, overconfidence can lead to complacency. By remaining focused and building on their early successes, boards can help their companies succeed—no matter how the pandemic unfolds.

As the pandemic and its economic impact continues to develop, PwC’s COVID-19 board resources website will continue to offer timely resources and perspectives to help boards guide their companies through each stage. In addition, our Emerge Stronger video series offers practical advice to take lessons learned from the pandemic, and turn them into valuable insights for use in your board oversight role.

Environmental, social, and governance issues

Directors start to come around on ESG

Institutional shareholders have continued to emphasize to their portfolio companies the importance of creating long-term, sustainable business models. As part of this, they have pushed companies to offer more disclosure of ESG metrics. And while the COVID-19 pandemic has shifted the economic focus in many ways, institutional shareholders remain committed (and may be even more committed) to the importance of managing ESG risks and opportunities in their portfolio companies. [1]

Although shareholders emphasize that ESG risks will impact the bottom line, directors are not convinced that they’re connected to the company’s bottom line. Only 38% of directors say ESG issues have a financial impact on the company’s performance—down from 49% in 2019.

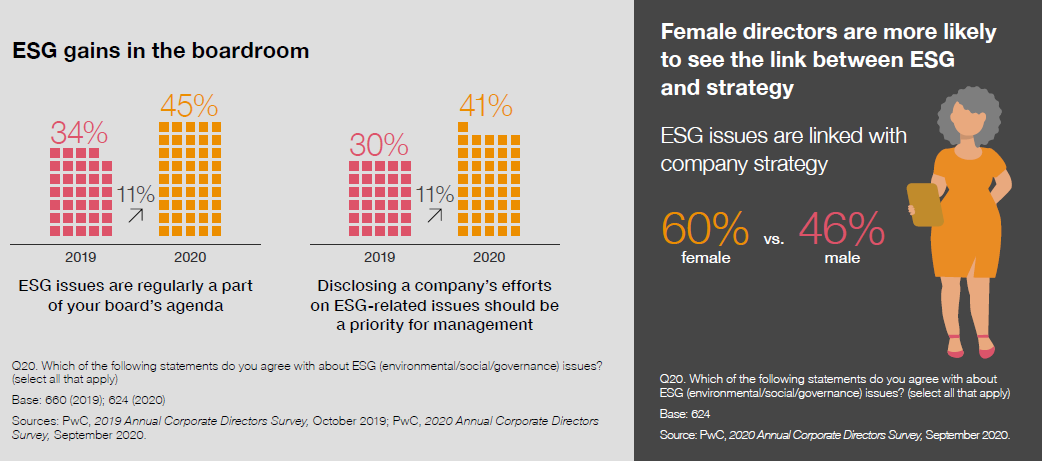

In other ways, directors’ practices and views are changing. In 2020, just under half of directors (45%) say that ESG issues are regularly a part of the board’s agenda, up from just 34% in 2019. Directors are also much more likely to say that disclosing a company’s efforts on ESG-related issues should be a priority for management.

That figure is up 11 points, from 30% to 41%. Directors are also giving greater weight to ESG expertise in the boardroom. The percentage of directors saying that environmental/sustainability expertise is important went up nine points, to 60%.

As companies are facing financial pressures from many sides during the continuing pandemic and economic recession, those that have taken a broader view of their long-term strategy, including responding to ESG issues, may be in a better position to confront these challenges. For companies that have traditionally focused on the narrow question of financial performance quarter to quarter, 2020 may offer the inflection point to consider the broader, long-term context.

PwC perspective

Taking on ESG oversight

For companies, ESG is about risk, and it’s about opportunity. It’s about the ways in which value could be destroyed or created. Boards play a critical role in ESG oversight. Those that are successful in that task focus on:

- Linking purpose and strategy. From the board’s unique vantage point, determine whether the company has appropriately articulated and defined its purpose, and whether that purpose is linked to and reflected in its strategy. Ensure that it is comprehensive and considers the right stakeholders.

- Requiring reliable ESG information. Companies can choose from a variety of disclosure regimes for their ESG information, and using the right metrics is key. Affirm that the information prepared by the company is consistent and reliable.

- Crafting the right disclosure. With purpose and strategy linked, and the right information available, the company can determine its key messaging. For the board, ensure that this messaging translates to the company’s disclosures. Ensure checks are in place on what information is disclosed, where it is disclosed, how it is reviewed, and whether it fully reflects the company’s purpose and strategy.

- Allocating oversight. Overseeing how the ESG strategy aligns with the company’s business strategy is a job for the full board. But each committee also has ownership over some element of ESG issues, and coordination and communication are key.

For more on understanding and overseeing ESG risks and opportunities, visit the ESG page on our website.

Thinking more broadly about strategy formation

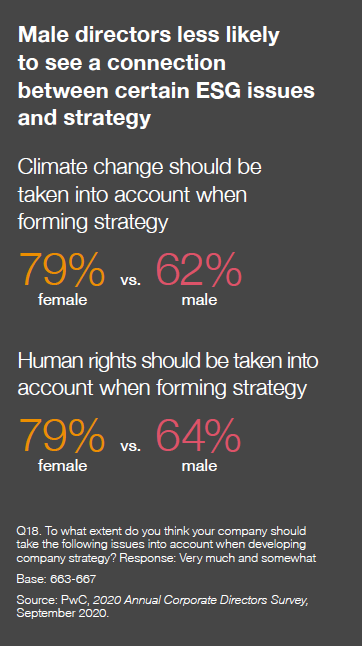

Directors say ESG issues are playing a larger role in their board discussions. They also increasingly think these issues should play a role in determining company strategy.

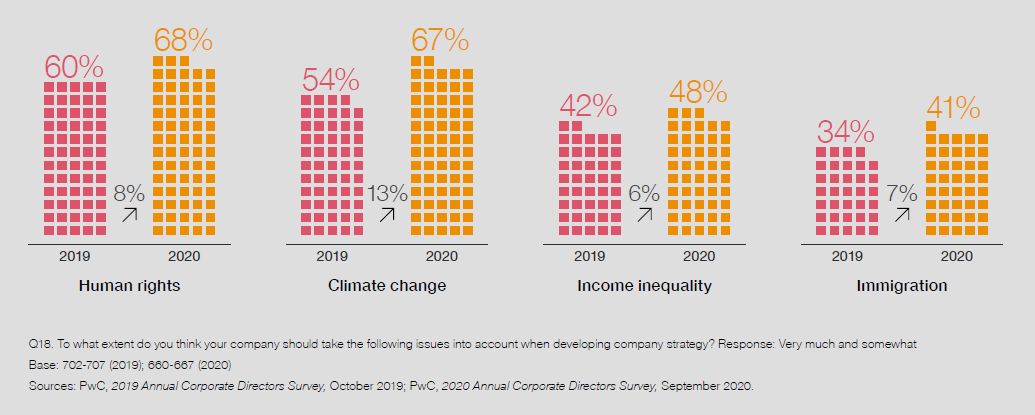

Issues of human rights, climate change, and income inequality are playing a bigger role in strategy. The percentage of directors saying that the company should take climate change into account when developing its strategy jumped 13 points in just one year (67%, up from 54%). The percentage of directors saying the same about immigration, human rights, and income inequality also increased since 2019.

But while more directors say these topics should have a role, the current economic downcycle may put boards to the test. While making it through the immediate crisis must be the first priority, boards can also take this opportunity to shift the conversation to broader, long-term concerns. Many companies will emerge from the crisis looking different. Now may be the time to work out how to incorporate issues like climate change and income inequality into their companies’ strategic goals—particularly as these topics remain top of mind for investors focused on the long-term viability of their portfolio companies.

Broadening the scope of strategy discussions

A rising percentage of directors think social issues should play a role in forming company strategy

Board diversity

Gender diversity ticks up, but male directors remain unconvinced

The representation of female directors on boards has increased steadily over the years, from 16% of S&P 500 board seats in 2009 to 26% in 2019. [2] While this shift reflects consistent pressure from institutional shareholders for boards to diversify, as well as measures like state legislation that requires public company boards to have female directors, the percentage of female directors is still only about half of their representation in the US population. [3]

Directors, for their part, agree that diversity on boards has benefits. Ninety-four percent (94%) say that it brings unique perspectives to the room. More than four out of five directors agree that it improves relationships with investors (85%) and that it enhances board performance (83%). Seventy-two percent (72%) also agree that board diversity enhances company performance.

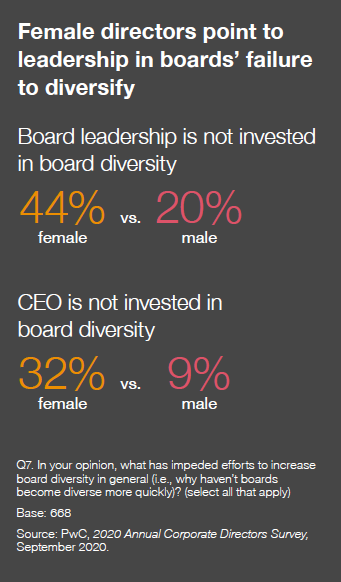

So if directors agree on the benefits, why aren’t boards diversifying more quickly? Female directors often point to leadership. They are more than twice as likely as male directors to say that board leadership is not invested in diversity (44% versus 20%). And female directors are more than three times as likely to say that boards are not diversifying because the CEO is not committed to the issue (32% versus 9%).

As boards confront questions about the very survival of a company during a public health and economic crisis, they may risk losing focus on critical board composition and diversity issues. But inflection points such as these can also provide the opportunity for leadership to take a bold step and invest in real change on the board.

PwC perspective

Boards and racial diversity

During the spring of 2020, the country faced a reckoning on racial justice different from any it had seen before. Polls suggest that 15 to 26 million people participated in Black Lives Matter protests in the weeks following George Floyd’s death, making it perhaps the largest movement in US history. [footnote no=4] Corporations got involved too—making statements, changing policies, and renewing commitments to diversity. But what is the role of the board?

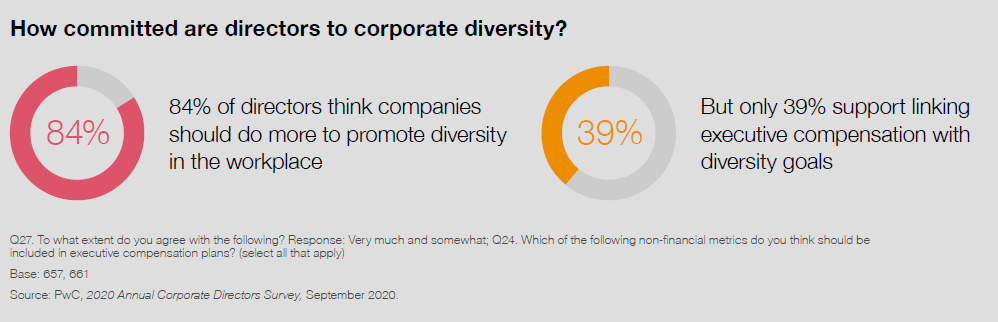

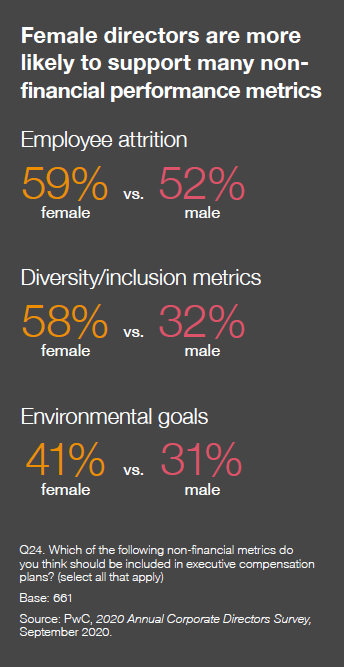

Generally, directors say they support corporate racial diversity. More than four out of five (84%) directors think that companies should be doing more to promote diversity in the workplace. Yet when it comes to actually tying executive pay to these actions, it’s a different story. Just 39% of directors think diversity and inclusion goals should be included in executive compensation plans.

What’s more, while most directors support doing more on gender and racial diversity at their companies in general, there is less support for change at the board level—especially when it comes to racial diversity. While less than half of directors (47%) say gender diversity is very important on their boards, only 34% say the same about racial diversity.

Stakeholders are demanding that corporate leaders in the US be part of the solution and take action to help dismantle racism and injustice. This can, and should, start with the boardroom. Boards can:

- Require standardized reporting on diversity and inclusion efforts. This can reveal trends at the company and help the board hold management to account.

- Ensure the company has created a strategic inclusion and diversity plan—and has shared that plan with the board of directors.

- Tie diversity and inclusion targets to executive pay.

- Take a look at the boardroom itself and whether it truly has a diverse set of voices.

Read Four Ways Boards Can Lead on Racial Diversity for more about boards’ role in this issue.

A move away from subject matter expertise

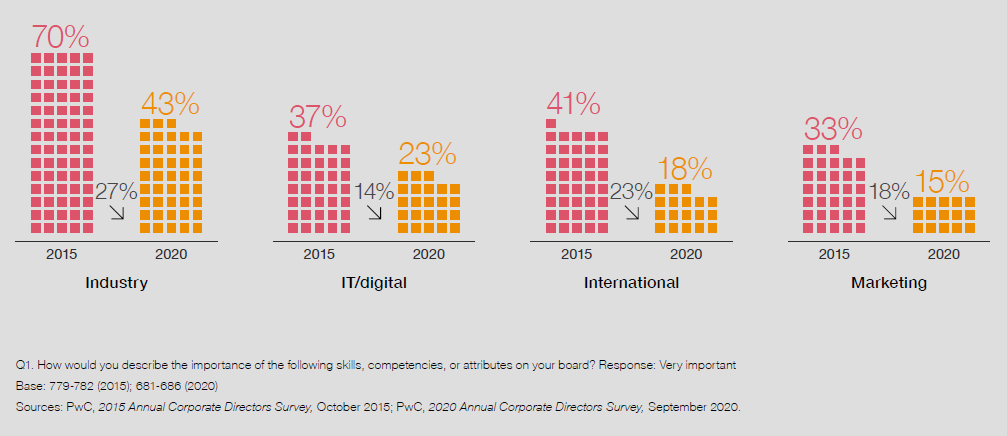

As shareholders push for more board diversity, they have also encouraged boards to think more broadly about how to create diversity of thought. As part of this, boards have been adding more female directors, and directors who bring racial diversity to the board. But they are also demonstrating a move away from the idea that they need certain subject matter experts.

Compared to responses five years ago, directors are much less likely to say that a variety of areas of expertise are “very important” to the board. They still highly value financial, operational, and risk management expertise. But, for example, the percentage of directors saying industry expertise is very important dropped by 27 points. International expertise and marketing expertise dropped by 23 and 18 points, respectively.

These drops may relate to the blurring of lines between industries, and the sense that most directors have broad experience. In addition, as boards focus more on diversity and the value of having the right mix of voices, people, and opinions, particular types expertise may be less important.

Fewer directors see value in specific areas of expertise

Board refreshment

Directors want refreshment, but boards fail to plan for the next chapter

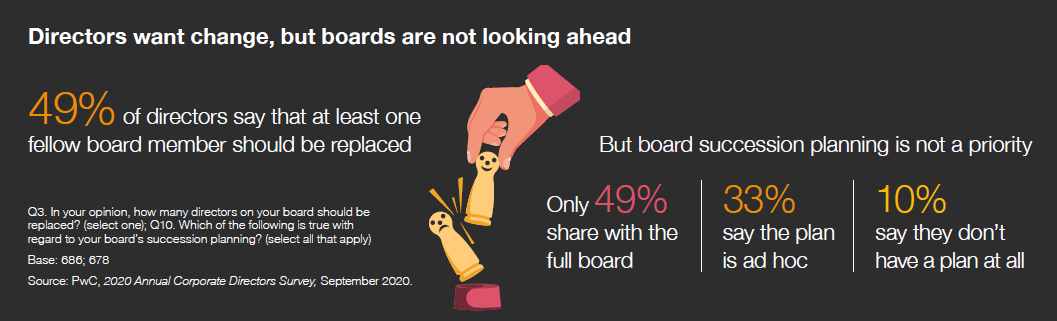

Boards are making strides in many areas, yet their own composition remains one of the toughest challenges for boards to confront. For the second year in a row, about half (49%) of directors say that at least one fellow director on their board should be replaced. Twenty-one percent (21%) say that two or more directors should go. These numbers remain high, despite intense shareholder focus on board refreshment.

What stands in the way of board refreshment? Many directors point to board leadership’s unwillingness to have difficult conversations with underperforming directors (20%) or to an ineffective assessment process (19%).

It’s also clear that director succession planning is not a priority for boards. Ten percent of directors say their board doesn’t have a succession plan at all, and 33% say it is ad hoc. For boards that do have a plan in place, less than half (49%) of directors actually share that plan with the entire board. So for many directors, they simply have no idea what the next chapter of the board will look like—and no input into those decisions.

Making real change in this area requires work from board leadership. It requires clear succession planning and open discussions with the entire board about what is to come. It also requires leadership to have hard conversations with respected peers. But 2020 may pose a unique opportunity for board leadership to push for change. For some, the early days of the crisis may have even highlighted shortcomings on the board. For example, boards with directors who are in sitting executive roles, or who serve on multiple boards, benefited from those broader insights.

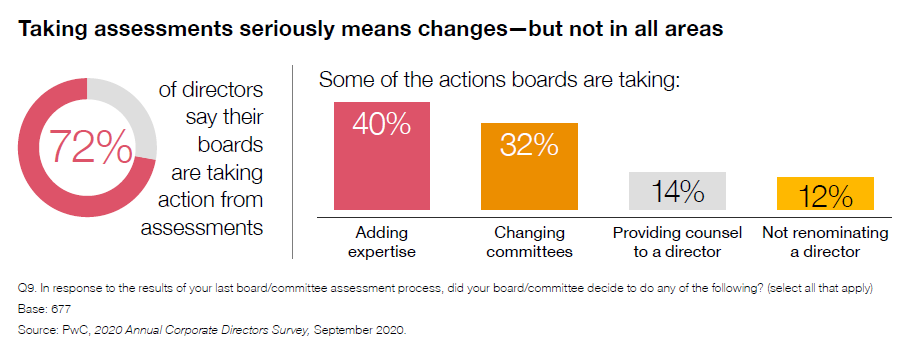

Boards sidestep the tough conversations

Once, performance assessments may have been seen as check-the-box exercises. Today, most boards take them seriously, and they take action as a result. In 2014, 50% of directors said their board made changes as a result of their assessment process. In 2020, that figure is 72%.

In response to their last performance assessment, 40% of directors say their boards or committees added additional expertise—an increase from 29% saying the same in 2014. Boards also commonly react to assessments by changing the composition of their committees (32%, up from 20% in 2014).

But boards aren’t seeing similar improvements when it comes to taking the toughest steps. The percentage of directors saying their boards chose not to renominate a director changed little since 2014 (12%, up from 9%). And only 14% say their board provided counsel to a director, down slightly from 16%. In fact, the area where directors give board leadership the lowest marks is in dealing with underperforming directors, with one in four (25%) saying leadership is not very or not at all effective in that area.

PwC perspective

Drive change in the boardroom by having the hard conversations

Like every other workplace, the boardroom looks different in 2020. The shift to virtual interactions may make conversations about the most difficult topics—like board refreshment—even more challenging.

But as boards face the unique challenges of 2020, it is more important than ever that board leadership addresses the issue of board refreshment. For boards that are not yet conducting individual performance assessments of each director, now is the time to institute the practice. And for board leadership who may have been avoiding the difficult conversations, now is the time to face that challenge. During this crisis, it is even more critical that boards be able to identify the directors who are not adding value. And board leadership must be willing to ask those directors to either change their behavior or make room for directors who will bring more to the table.

Board practices

Holding their tongues when they disagree

Board oversight means asking the tough questions, demanding answers, and arriving at sometimes uncomfortable conclusions. To do that, the boardroom requires honesty and frank discussions.

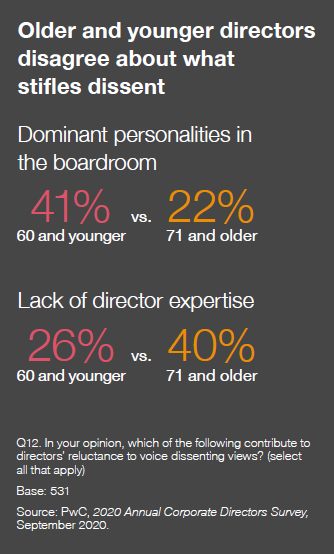

Yet directors privately confess that they hold back dissenting views. More than one-third of directors (36%) say that it is hard to voice a dissenting opinion in their boardroom.

For many directors, the problem traces back to the fear that dissenting opinions will damage collegiality in the boardroom. Fifty-two percent (52%) of directors say that the desire to maintain a collegial atmosphere contributes to muffled dissent. Thirty-two percent (32%) say it stems from dominant personalities in the boardroom.

As the COVID-19 pandemic and accompanying economic crisis exposes weaknesses in companies and entire industries, boards’ leadership is more critical than ever. The disruption in business as usual creates an opportunity for board leaders to shift the status quo. With everything else changing, board leaders can use the moment to encourage a new level of openness and honesty in their discussions.

PwC perspective

Overcoming the hidden dynamics holding boards back

Board members are highly educated, accomplished, successful individuals. Yet every director has witnessed derailed discussions, dismissed opinions, directors who dominate, and those who seem to be biting their tongue. Many of these problems can be traced to four common biases we see in boardrooms.

- Authority bias: Overvaluing the opinion of one director with a particular set of skills or experience, or a director in a leadership role.

- Groupthink: Being overly concerned with coming to a consensus.

- Status quo bias: A reluctance to change the way things are.

- Confirmation bias: The tendency to overvalue evidence that confirms one’s view, while undervaluing evidence that disproves it.

For much more about boardroom biases and tools to improve boardroom culture, look for our forthcoming paper Effective board culture: The hidden dynamics that hold boards back—and how to overcome them.

Shareholder engagement continues to bring benefits

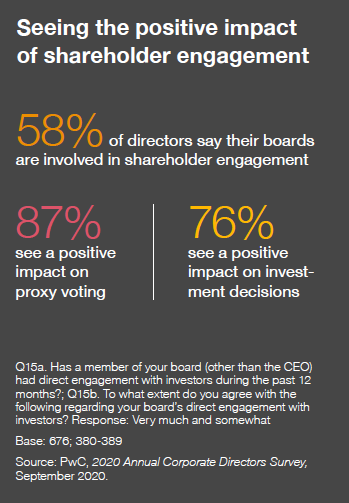

Investors have increased their focus on shareholder engagement in recent years. Large institutional shareholders, in particular, have made it a priority by beefing up their stewardship teams and increasing the number of engagements they conduct every year.

At the same time, director involvement in shareholder engagement continues to grow. In 2020, 58% of directors say a member of their board (other than the CEO) is involved in these discussions, up from just 42% in 2017.

As the practice continues to grow, directors see the effect. Eighty-seven percent (87%) think the engagement has a positive impact on proxy voting, up from 59% in 2016. More than three-quarters (76%) also see a positive impact on investing decisions, up from just 63% four years ago.

Companies that took shareholder engagement seriously over the past several years may be seeing those dividends now. By building shareholder relationships with their most important investors during the “calm times,” companies may find that having that existing connection is more important than ever as they are put to the test in 2020. Shareholders will likely be pushing companies to address topics like strategy adjustments, changes in capital allocation, and executive compensation design before the 2021 proxy season.

Spotlight: Corporate reputation and personal reputation merge

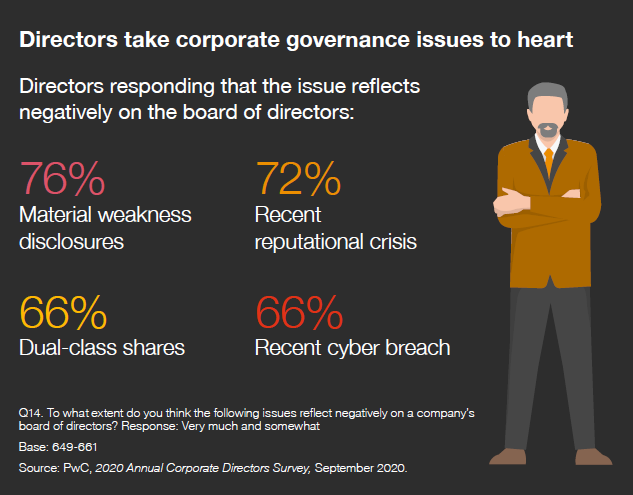

For directors, board service can go well beyond just fulfilling a professional duty. Many feel a strong connection to the company, associating their personal brand with that of the company. They see the company’s governance decisions and major events as a reflection of themselves.

A majority of directors say that issues like disclosing a material weakness (76%) or going through a recent reputational crisis (72%) reflect negatively on the board members themselves. These are issues that perhaps the board may feel some responsibility for preventing. A majority of directors also feel that having a dual-class share structure or experiencing a recent cyber breach (both 66%) reflect negatively.

With directors associating their own reputation with that of the company they serve, it’s clear that the connection is strong. They may have more at stake in their role than many investors give them credit for.

Culture and talent management

Taking action on company culture

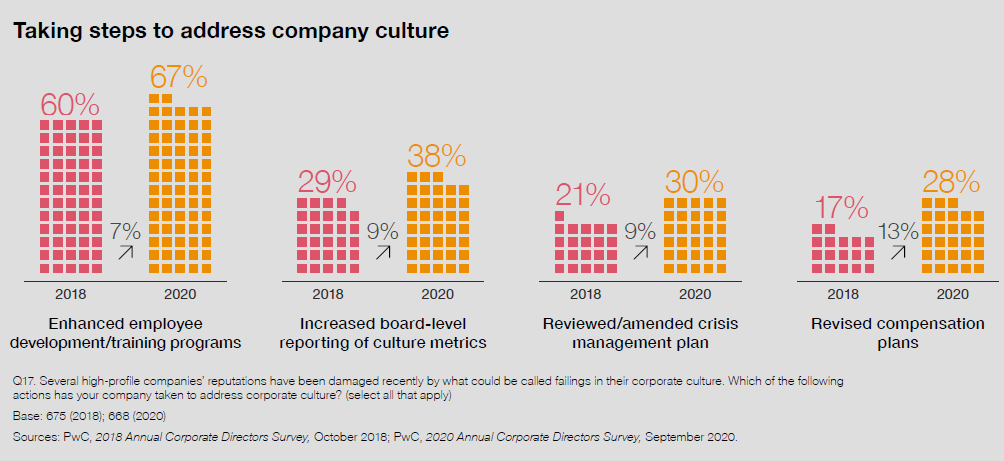

The risks posed by problematic company culture came into the spotlight in recent years. High-profile cheating scandals, corporate misdeeds, and movements like #MeToo forced many companies to re-examine how their own cultures could be contributing to problems.

Over the last several years, many more directors say their boards are taking a variety of actions to address corporate culture. Most commonly, companies have enhanced employee development and training programs. Two-thirds of directors (67%) say their companies have taken this step, up from 60% in 2018. More directors also say their companies are increasing reporting to the board about culture metrics. This could include employee engagement survey results, media coverage, or hotline trends, which can give a data-based view of an inherently ephemeral topic.

More directors also report reviewing or amending their compensation plans. By re-examining how their plans motivate employees, they may uncover some root causes for problematic behaviors and be able to adjust accordingly.

As many companies struggle with the challenges posed by balancing employee and customer safety with business needs, navigating remote work environments and a radically different view of the workplace, the issue of company culture will be even more challenging. In addition to the question of whether the company has the right culture, boards will also be grappling with how to define, build, and sustain a corporate culture at this moment.

When it comes to executive pay, how much is too much?

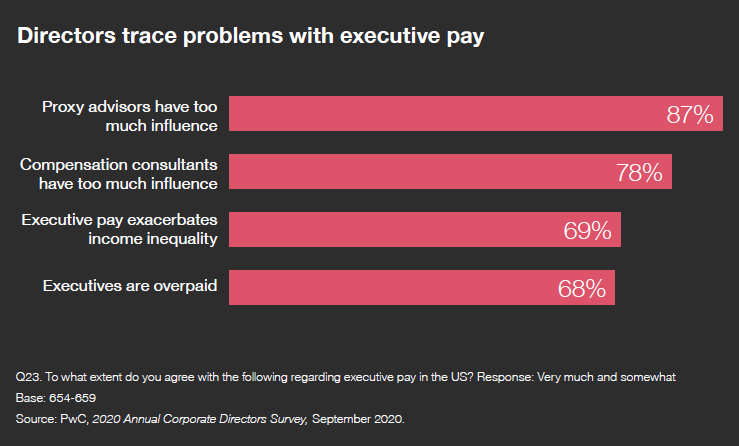

At a time when the US has experienced record-high levels of unemployment and economic uncertainty, directors also see issues with excessive executive pay. While nearly all directors (95%) at least somewhat agree that incentive pay plans promote shareholder value, 69% also somewhat or very much agree that executive pay exacerbates income inequality.

Directors continue to view proxy advisors and compensation consultants as having too much influence on executive pay, but many put at least some of the blame on the board as well. More than half (60%) at least somewhat agree that compensation committees are too willing to approve overly-generous pay packages or incentives. More than two-thirds of directors (68%) think that executives are overpaid, and 52% think targets are too easy to achieve.

The current climate is forcing boards to take a hard look at executive pay. Plans and targets that were reasonable earlier in the year may not make sense by December. With many companies experiencing uncertainty and volatility, boards may worry about executive retention if appropriate incentives are not in place. At the same time, the optics of these decisions, and of overall pay numbers, are key. Companies and boards will need to focus on transparent disclosure of what steps they have taken, and why, in order to convince shareholders that they’ve made the right decisions during turbulent times.

Taking a broader view of incentive pay—in some areas

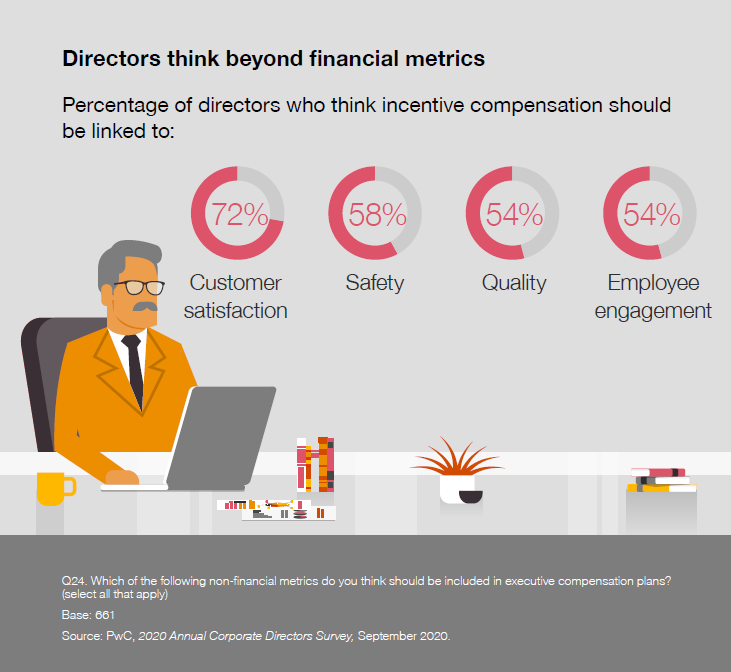

As the idea of corporate purpose has pushed companies to think beyond just the bottom line, directors are also rethinking how to measure performance.

While most directors do not support having diversity and inclusion goals as part of executive compensation plans (see page 12), they do support a variety of other non-financial goals. More than half of directors think customer satisfaction (72%), safety (58%), quality (54%), and employee engagement (54%) should be a part of the calculation.

During tough times, compensation committees still need to keep their executives incentivized. With the business climate changing so rapidly in 2020, boards have the opportunity now to reconsider the future of the company and to create the right incentives to encourage management to get there.

Endnotes

[1] For example, see a discussion of BlackRock’s 2020 Investment Stewardship Report available here.(go back)

[2] Spencer Stuart, 2019 U.S. Spencer Stuart Board Index, October 2019.(go back)

[3] See the US Census Bureau’s website here.(go back)

[4] Larry Buchanan, Quoctrung Bui and Jugal K. Patel, “Black Lives Matter May Be the Largest Movement in U.S. History.” NY Times, July 3, 2020.(go back)