Fuente: Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance

Autor: Peter Gassmann and Will Jackson-Moore, PricewaterhouseCoopers

A consensus has emerged in recent years that environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues are crucially important for the corporate world. But what should companies do about investors who won’t accept lower returns in order to further ESG goals?

In a recent PwC survey, global investors placed ESG-related outcomes such as effective corporate governance and greenhouse-gas emissions reduction among their top five priorities for business to deliver. But 81% went on to say they would accept only a 1 percentage point or smaller reduction in returns to advance ESG objectives—both those that are relevant to the business and those that have a beneficial impact on society. And roughly half of that group were especially unyielding and would not accept any decline in returns at all.

For chief executives and boards, the disconnect with investors presents a dilemma: can their company perform well for investors and pursue a clear ESG strategy at the same time? We believe the answer is yes, if companies find the right balance between short-term performance requirements and the investments needed to meet longer-term ESG goals. To be sure, as companies invest in ESG initiatives (for example, in the technologies and systems needed to support future regulations and any net-zero commitments they have made), they may face pushback and short-term share price swings. But in the long run, as climate change increasingly affects value preservation and the ability to deliver sustained profits, the total accumulated value of not investing in ESG will be significantly lower than a successful ESG approach. The key is to define a convincing long-term ESG path to create value within the boundaries of the short-term KPIs that address investors’ performance expectations. Taking their stakeholders—and in particular their shareholders—along the journey toward that longer-term vision is how companies can address the disconnect between short-term pressures and longer-term opportunities.

The narrative of that journey must demonstrate considerable coherence, which can emerge only as companies find their best-fitting strategic stance on ESG and tie it explicitly to value creation. Companies that pursue a strategically clear stance (or true north) toward ESG can help investors and other stakeholders understand the boundaries or guardrails of their company—what they’ll do with regard to ESG, where they’ll play, and which capabilities they’ll develop themselves (versus looking to ecosystem partners to provide), while clarifying decisions and resource allocation. Because a good articulation of your true north helps make clear the unique value your company creates for customers and society, it enables the creation of the coherent narrative investors need. Is your entire corporate strategy defined by ESG? Is your strategy to simply conform with legal and regulatory requirements? Or is your stance somewhere in between?

Getting your ESG stance right helps you think through another key consideration: the business ecosystems of which you are and should be a part. Why ecosystems? Because competition is increasingly won or lost on the basis of ecosystems. These networks of companies and institutions help coordinate multiple participants, which may offer the only way to tackle complex, far-reaching challenges such as ESG (in part by helping mitigate strategic, regulatory, and other forms of risk). Ecosystems are growing ever more relevant to how companies create and capture value. Yet many of the ecosystems needed to advance ESG goals—such as those in transportation and energy, or those working to reduce Scope 3 emissions in supply chains—are only in the early stages of formation or will need to be built from scratch.

To shape the development of new and existing ecosystems and access the value pools emerging around them, many companies will need to develop, perhaps for the first time, the ability to manage the interplay between their organization and the ecosystems in which they participate. This ability goes beyond the ad hoc approaches to partnering most companies have taken in the past. In this article, we’ll describe how to get your strategic stance right and how to build the ecosystem capabilities you need to handle ESG risks and target emerging pools of value.

The good news is that by participating in ecosystems, you don’t have to provide and scale all the capabilities for ESG on your own. You can access the capabilities others are building—the complex combinations of talent, technology, processes, and insight that ecosystem partners provide. Once you do, you can look to refine the ways in which your company represents itself to investors and other stakeholders. In the ESG world, as elsewhere, winning narratives help mobilize investment and ecosystem participants in commonly beneficial directions.

Momentum is building as major ESG success stories develop. Look at Neste, an oil refiner and marketer based in Finland that has made a big push into renewable fuels. It formed a high-profile partnership with McDonald’s and built an ecosystem around it—one company collects the oil used by McDonald’s for frying, along with other animal fat waste; another transports it to Neste, which processes the materials into diesel fuel that it then sells to a trucking company partner. Neste has since established similar partnerships to collect used cooking oil, including with Dallas–Fort Worth Airport. Neste also invested €1.4 billion (US$1.37 billion) in a refinery in Singapore to increase the company’s output of renewable fuels by as much as 1.3 million tons a year. Such investments have let Neste revamp its brand and develop the narrative needed to be seen as a sustainable company that is pioneering ways to turn food waste into a feedstock.

But your own success story starts with defining your strategic stance toward ESG. That’s where we’ll dive in first, before helping you think through your ecosystem approach, the capabilities you need, and the narrative you’ll construct to represent it all.

Finding your true north

ESG has been building as a key topic for nearly 20 years, at least since the topic was mentioned in a 2006 United Nations report on principles of responsible investment. Attention has intensified as evidence of climate change has increased. The growing attention and urgency not only raise concerns about the E in ESG but also add to interest in whether companies are being responsible social citizens and applying governance practices that conform with both the letter and the spirit of government regulations.

The need to focus on ESG will only mount. As more governments have committed to net-zero targets, regulators are stepping up pressure for businesses to be more sustainable. Investors likewise say they prefer to put money into businesses with a strong ESG profile (even if investors aren’t yet willing to sacrifice much return to do so). Increasingly, customers, employees, and potential employees are evaluating companies on ESG criteria, urged on by activists and other social forces.

As time has passed, companies have realized that an emphasis on ESG issues isn’t just an excuse for scolding them. Widespread interest in the environment and social and governance concerns also opens up enormous opportunities. If your company invented a polymer that could be used in all plastic containers for consumer products, which would greatly simplify recycling, then you could win in a massive market. You’d also get a reputation as a superb corporate citizen, which would help not only with customers and investors but with the talent you want to attract, and you’d garner favorable attention from government regulators.

But you first have to figure out what your authentic identity, your true north, is in terms of ESG. Your true north, in the general sense, is what you believe is the unique core value that you bring to a set of customers. This value isn’t a short- or even a mid-term plan or a new product initiative. It’s a sense of where you fit for a decade or for multiple decades. You need to take that same sort of long-term view about ESG and decide how closely its considerations align with your true north.

To find your true north, decide which of four ESG stances fits you. Are you, for the long haul, a conformist, a pragmatist, a strategist, or an idealist? “What’s your strategic stance toward ESG?” shows these archetypes along a spectrum.

Once you have defined your ambition level for ESG, you can consider which issues to focus on. Waste reduction and circularity? Fostering biodiversity? Fair rights? Digital cybersecurity? Selecting the right ones requires coming to terms with the current and potential future impact of external factors on your industry. Even deciding that you’re, say, a pragmatist can have major implications. If you’re a fossil fuels company, for example, you might be considering a scenario in which environmental concerns will reduce demand for oil, and in which new materials could even render oil and gas companies’ reserves obsolete over the next several decades. A pragmatist in that industry would be exploring alternatives even now. Otherwise, the company could end up developing an awful lot of oil and gas “reserves” that will never come out of the ground.

Idealists such as Patagonia and Honest Tea will be acting sooner and more aggressively than others. Though Honest Tea obviously needs to focus on the taste of its products, its second core tenet is to be environmentally responsible and to create economic opportunities for its suppliers, many in developing countries. Patagonia’s mission statement is: We’re in business to save our home planet. That goal affects everything from how the company sources, makes, ships, and sells its products to how it engages with employees and partners.

Your true north tells you the direction you want to go on ESG and helps define your volume of investment and the ESG narrative you want to embrace and communicate. You’ll need clarity on these elements of your approach to ESG, even if your strategic stance is simply that of the “conformist” rather than a more ambitious one. Your true north also helps you see which ecosystems you should participate in or perhaps help develop.

Finding your true north results in a consistent set of statements that help establish the guardrails of what you’ll do with respect to ESG, where you’ll play, and which capabilities you’ll develop yourself (versus looking to partners to provide)—statements that clarify decisions and resource allocation, and make it easier to create the coherent narrative investors need if you are to overcome the ESG dilemma discussed at the top of this article.

Making a successful ecosystem play

Even a pragmatist, like a fossil fuels company studying whether environmental concerns will depress demand, can’t go it alone. The shift isn’t just a change in material from oil to non-fossil-based fuels, from coal for power plants to solar and wind. Changes in consumer behavior will also need to be taken into account, requiring collaboration with a host of companies that touch consumers; products and services will need to be redesigned from the start, also requiring a range of new connections and collaborations.

In many cases, the ecosystems needed to deliver on the true north that companies have defined don’t yet exist. Consider a car manufacturer that is expanding into electric vehicles, on the basis of both pragmatic considerations about tapping into a burgeoning market and an array of concerns about the environment; it is also mindful of the social concerns of customers, communities, and employees and of the governance practices it needs to respond ethically to government regulations on pollution. To fulfill its ESG goals, that company can’t just produce an electric car. It needs to think through upstream and downstream concerns, too.

Upstream, there currently are problems with the mining of key materials for batteries, which can occur in ways that damage the environment. These materials are also provided by countries where trade relations may be complex (such as with China) or where conflicts, displacement, and economic stability are an issue (such as the Democratic Republic of Congo). That carmaker may want to find new sources for lithium, cobalt, rare earth metals, etc., and may even want to try to develop new types of batteries that don’t need such materials.

Downstream, the car company hopes to ensure that its vehicles can be recycled—but is aware that the components aren’t currently designed for that. The metal can’t easily be separated from the plastic in the batteries, for example, or the wall of the battery cell. The car company will need to engage with its ecosystem so that a vehicle flows as seamlessly as possible from a lifetime of use into a recycling process that lets its key components be separated and reused. The carmaker will, in some cases, need to find partners that will invent materials, processes, and materials processes that make that recycling easier.

Opportunities for new ecosystems abound as companies pursue ESG goals. For example, a host of companies are working together on an initiative for low-carbon-emitting technologies (LCET) to be established by the end of 2023. Air Liquide, SIBUR, Dow, BASF, Clariant, SABIC, DSM, Mitsubishi Chemical, Solvay, and Covestro have all signed up. Even direct competitors will find reasons to collaborate; for instance, Allbirds and Adidas are working together on how to reduce carbon emissions across the whole shoe process, from manufacturing to packaging and shipping. There is even a new sort of buyers’ cooperative forming—more than 50 companies have joined in the First Movers Coalition to guarantee an early market for technologies that could help get the world to net zero by 2050 but that are too expensive in their early stages to generate much demand on the open market.

Other ecosystems will have to develop or continue to develop. For instance, in transportation, ecosystems are developing relating to micromobility, electrification, infrastructure for charging and refueling with hydrogen, sustainable aviation, and more. Consumer goods will need ecosystems for packaging, delivery, materials, and labor inputs. Agriculture requires ecosystems for fertilizers, farm equipment, alternative meats, and other proteins. And those are just the start.

How do you help these ecosystems develop and get where they need to be to support your strategic ESG stance while playing a significant or even leading role yourself? Several elements are crucial for flexibility and agile steering.

Map the influences

ESG ecosystems represent dynamically evolving relationships between companies and their external stakeholders. Some stakeholders are in your immediate environment, such as the suppliers, competitors, and customers that directly influence business operations. Others, such as NGOs, regulators, and investors, live in the broader macroeconomic environment. You’ll want to map the overlapping, sometimes competing objectives of these external influencers, paying close attention to which relationships offer access to shifting value pools and complementary capabilities.

The idea here is to gain clarity and avoid surprises. Is a critical supplier’s ambition to design fully circular products only, which will come with certain requirements and expectations? Will the formation of a partnership involving hydrogen use in your industry increase expectations of green energy use? What if the European Union announces new legislation for diversity on company boards starting in 2030, or sooner?

Investor movements and trends regarding ESG seem particularly fluid and may require fine segmentation to retain the optimal investor mix as investors adapt specific investment styles such as ESG rebalancing, social-impact investing, and thematic focus on any of the E, S, or G components. Your ESG narrative, which we’ll discuss below, will likely need to be equally granular.

For public companies, the stock price will indicate whether the company’s goals are aligned with those of investors, obviously a crucial issue. But companies will also have to develop a deep understanding of the needs of customers and other stakeholders. In the past, companies often relied on others for that deep understanding. A company such as Shell, for instance, was a feedstock supplier and was far away from the end consumer, so it counted on intermediaries to translate consumer needs. Nowadays, disruptions occur so fast that a company such as Shell must track and understand stakeholder needs directly.

Get the capabilities you need

Many of the unresolved challenges the world faces in the ESG domain are so big and complex that no company on its own can solve them. They can be addressed only by networks of companies and institutions working together toward a common purpose. [1] That’s because no single company has the resources to develop the capabilities required, nor could it scale them as quickly as the dynamic world of ESG demands.

Because ecosystems allow companies to access the complementary capabilities of partners, it’s critical to understand your current capabilities, what you can develop yourself, and which capabilities or value delivery vehicles you’ll need from your ecosystem. That means sorting out, first, which capabilities are needed to address areas of ESG relevant to your stakeholders and your ecosystem’s stakeholders and, second, which of them you yourself will provide and which you’ll look to your ecosystem partners to contribute and deliver together with you.

One place to start is with a capabilities assessment tool that can help define your table stakes versus your differentiating capabilities. Tools like these can shed light on how well aligned your people and your financial resources are behind your most important capabilities, and how close your company is to having best-in-class capabilities, allowing you to shed weaker capabilities with negative ESG impacts and cultivate positive capabilities in which you’re better differentiated. Then, perform the same analysis for the ecosystem you’re looking to join or help develop by assessing the technologies, capabilities, and access to new value pools they offer, as well as their previously existing alliances.

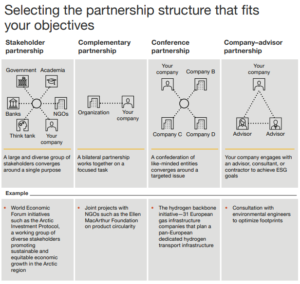

Once you’ve identified potential partners, choose the right partnership structure with which to engage them. “Selecting the partnership structure that fits your objectives” describes four approaches.

Choices about whether and where to build capabilities will vary, of course. Rügenwalder Mühle, a nearly 200-year-old German company that specializes in sausages and other meat products, decided to strengthen its own capabilities to reorient customers toward a vegan meat alternative after the company began selling meatless products in 2014. In another example, BASF decided to use its ecosystem to enhance its capabilities in chemical recycling.

The key will be to reevaluate capabilities within the context of your ESG strategy. This will require making the most of the latest scenario-modeling techniques while building the capabilities needed for nimble responses to a shifting technology, regulatory, and market context. For example, many of the best solutions and approaches to ESG challenges—such as the exact path of decarbonization or how new technological breakthroughs might affect the mix of future energy sources—have yet to be developed. Nor are future regulatory scenarios fully clear. At the same time, companies need the ability to move quickly to respond to short-term geopolitical and other challenges. And then to move quickly again and again.

Build the trust that makes it work

As in a marriage, trust between partners is fundamental. Trusting your ecosystem partners requires a profound understanding of what motivates them and why they operate as they do. Companies in lightly regulated industries, for example, will have different cultures, business practices, and processes than those in more highly regulated industries. You can’t work effectively with organizations you don’t understand. It’s worth the time and effort to really get to know your ecosystem partners.

After all, networks of businesses are referred to as ecosystems for a reason: they resemble ecologies that are home to multiple species whose success is a collective process. Business ecosystems require shared practices and processes, face-to-face interactions (sometimes through shared office space or colocation), and reciprocity. One element of reciprocity has to do with economic incentives: thriving ecosystems are those in which everyone—but most importantly, the company playing the orchestrator’s role—focuses on growing the whole pie, not on securing the biggest slice for themselves. Ecosystem participants create and capture value together, even as they share risk.

Making and living up to small, ongoing commitments is another aspect of reciprocity, one that plays an important signaling role to partners and ecosystem participants. If your company intends to play the orchestrator’s role, signaling your commitment (for example, by making investments that indicate your intention to play for the long haul, regardless of temporary setbacks and obstacles) helps attract ecosystem participants and encourages them to make complementary investments.

Plan for the end

The average tenure of a corporate executive is about five years. The average duration of a strategic alliance is only four. Before making an alliance, companies should assess the alignment between the strategic ESG stances of each of their potential partners, and of all of them together. Wise partners will consider the circumstances that might lead to dissolution, which can include a changing business environment, the emergence of new potential partners, and the development of new capabilities by one or more of the partners themselves. Having made this consideration, they should look to agree up front on what mechanisms govern under which circumstances, and when the alliance can be dissolved, as well as what will happen to any assets and people once the partnership is no longer in effect.

Nurture your ecosystem culture

One of the most difficult elements of building an ESG ecosystem has to do with constraints in your own company’s organizational culture. Though companies are accustomed to working within their own four walls and having considerable control over resources, ecosystems require different levels of transparency and collaboration, some of which may run counter to your company’s established approaches and dispositions. You may need to share data that you long considered proprietary. You may choose to include employees from partners on your internal teams or send some of your employees to work in their offices—knowing full well that some of your talented people may leave you, at least for a time, to work full time for that partner. All of this may seem counter to your existing organizational culture.

ESG requires nurturing culture across and beyond institutional boundaries to bring together a network linking and connecting government, business, philanthropy, academia, and civil society, such as the India Climate Collaborative, which was launched by corporate leaders in that country. Ecosystems that combine public–private partnerships require joining different organizational cultures, such as the sustainability-focused advisory firm Systemiq did when it brought together public and philanthropic capital to address a lower-carbon food system.

The power of authentic narrative

PwC research shows that the companies that reallocate capital more frequently tend to perform better than companies characterized by higher levels of inertia, so the bias should be toward action. If you wait, you’ll have more certainty, but you may have missed out on the best opportunities.

But we realize that many early investments won’t pay off. We also remember the starting point for this article: that investors are loath to take a haircut on their returns even as they say they support ESG agendas.

A coherent narrative is the way to start to tie all the pieces together. You need to begin with your authentic identity. You should then craft a narrative based on the needs of your stakeholders, likely beginning with those investors who are leery of lower returns but extending broadly to include customers, employees, communities, and government interests. The narrative should include facts and targets, but you have to get to the emotional core as well—the urgency, trust, value, transparency, and hope of your ESG strategy. Though you will be tempted to overpromise, there can’t be any say–do gap. Greenwashing will be spotted soon enough, and you’ll lose your credibility.

Note that narratives work at multiple levels—craft yours for investors, employees, stakeholders, and, crucially, those that need a coherent vision for where things are headed if they are to join the ecosystem and commit their resources and capabilities.

Note, too, that your narrative will likely lead you toward a change in how you think about doing business. Instead of short-term profits, you’ll focus more on long-term value, which will include environmental and social value, not just financial performance.

Your narrative will need to retain some flexibility. In a fast-moving world, all businesses face uncertainty. But the ESG environment is particularly fluid. Regulations are shifting. Technology is developing. Markets are nascent. And ecosystems are emerging. As the world changes around us, the needs of your stakeholders will change, too. So you’ll need to be prepared to adapt your products and services, along with the capabilities that support them and along with the ecosystems that both help you develop those capabilities and help you deliver your products and services to the market.

Investors will still have their requirement on short-term returns, but you’ll be able to explain how some series of initial investments—with potentially significant returns—fit into a compelling story line, with clear and acceptable effects on short-term performance expectations. And you’ll have created a road map to help you sequence an aggressive approach to the opportunities of ESG, one that will reward not only your investors but all your many other stakeholders, while delivering far greater value to society as a whole.