Fuente: McKinsey

Autores: Celia Huber, a senior partner in McKinsey’s Silicon Valley office; Greg Lewis, a part-time lecturer in business administration and strategy at the Ross School of Business and a senior adviser to McKinsey; Frithjof Lund, a senior partner in the Oslo office; and Nina Spielmann, a senior expert in the Zurich office.

Directors are spending more time on their work, yet few say their boards are better at creating long-term value. Survey data highlight the operating models that correlate most with value creation.

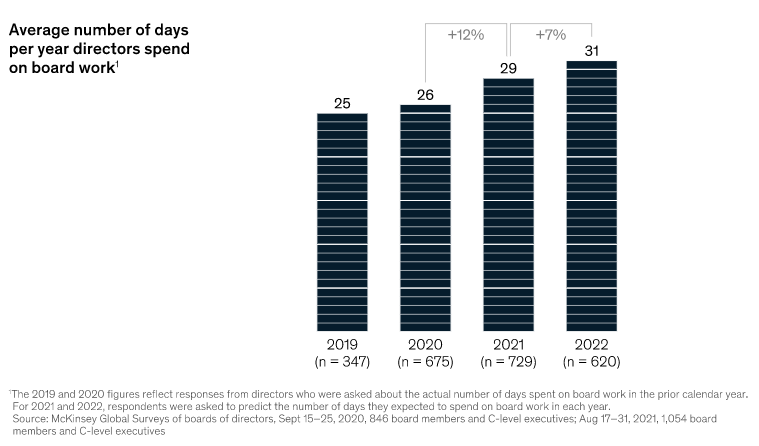

Over the past two years, company leaders have faced unprecedented management challenges in multiple dimensions of their business, and our ongoing research indicates that many board directors have risen to the occasion. In our newest McKinsey Global Survey on boards,1 directors report both a growing number of days spent on board work and that they expect to devote even more time to board work this year than they did in 2021 (Exhibit 1).

Yet despite that additional time spent, many directors do not report a corresponding increase in their boards’ overall impact on value creation. Between our 2019 survey (conducted a few months before the pandemic) and our newest research, the results suggest no material change in the impact that a board’s decisions and activities have made on their organizations’ long-term value creation.2

Of course, the COVID-19 pandemic’s prolonged volatility has hindered every board’s ability to plan and create value for the long term. But directors’ awareness that they need to invest more time in their work raises the question: How can they spend that additional time most effectively to secure their organizations’ long-term prosperity?

The operating models that support board impact

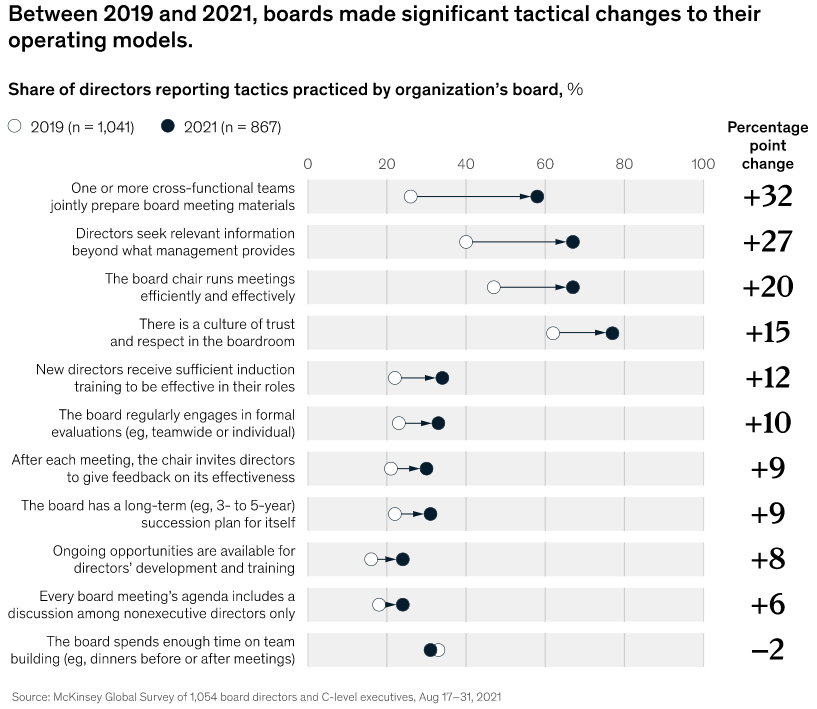

The survey asked about 12 key aspects of boards’ operating models. Based on our work with boards, these are the elements that more active and involved boards are pursuing. The majority of them have become more commonly implemented at respondents’ boards since the COVID-19 pandemic began (Exhibit 2).

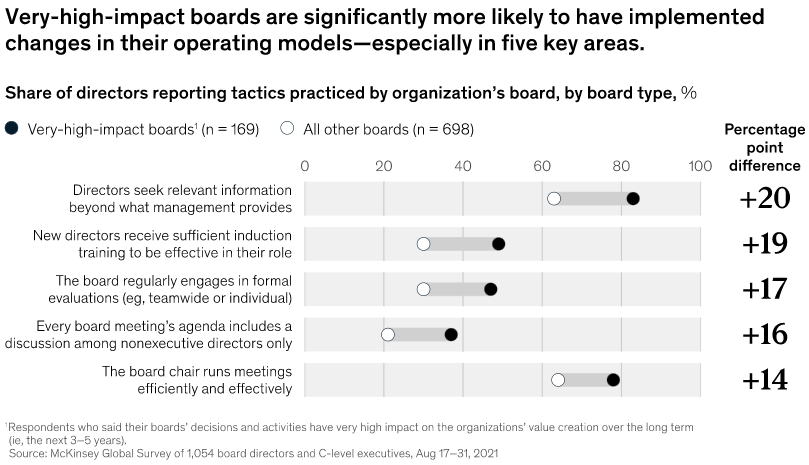

This is especially true among the “very high impact” boards, where directors say their decisions and activities have a strong influence on the organization’s value creation.3 We identified five changes to these operating models that very-high-impact boards are significantly more likely than others to have made. This, in turn, suggests which aspects of the operating models other boards would do well to revisit to increase their overall effectiveness as organizational leaders and as stewards (Exhibit 3).

To make these five changes to boards’ operating models—and to do so effectively—we recommend the following, based on our experience:

- Seek company information more proactively. At most organizations, the management team provides its board directors with access to a range of relevant materials and insights—usually in the form of board reports—before every board meeting. In most jurisdictions, board directors are also legally empowered to ask for any other information that would inform their perspective or decision making on a given topic. The survey results suggest that directors on the highest-impact boards have been doing just that, much more so than they did in 2019 and when compared with their peers: 83 percent now say their board members seek relevant information beyond what management provides, compared with 63 percent on other boards. This practice enhances a board’s potential impact by increasing board members’ familiarity with the organization’s overall context and the particular situation at hand, and also signals to the management team that the directors are making the effort to learn and contribute as much as possible. The board members who do seek additional information are better prepared to participate actively in discussions, to ask good questions, and to review the management team’s proposals more constructively and critically.

- Invest time in onboarding. Regardless of a new board member’s background, learning curves tend to be steep at the beginning of one’s tenure. It takes time to learn an organization’s strategy, culture, and overall ways of working—including how the board itself operates. Thorough, focused onboarding processes help board members learn quickly, so they can make effective contributions sooner rather than later. In our experience, an effective onboarding program is comprehensive and also partially tailored to the needs of a new director. For example, a director with little prior knowledge of the sector would benefit from receiving an in-depth industry perspective as well as current information on the company’s strategic direction, a summary of important board discussions from the past two years, and a personal introduction to key stakeholders, including the management team, all other board directors, and major shareholders or investors.

- Increase the cadence of board evaluations. While an annual performance evaluation is recommended for boards in most jurisdictions, in our experience, few board members actually engage in regular, formal evaluations—whether individually or collectively. A board’s performance can vary greatly over time and depends on several factors, including the chair’s leadership, the board’s overall composition, and the economic life cycle of the organization. According to the survey, the highest-impact boards are more likely than other boards to regularly examine their performance and have increasingly engaged in formal evaluations since 2019. In our view, it’s best if boards conduct a more in-depth evaluation of their overall team performance at least once per year—for example, through interviews with all directors—and complement this effort with regular feedback sessions after every meeting.

- Create space for nonexecutive voices. Giving independent directors the opportunity to discuss board topics among themselves increases accountability for both the board and the organization as a whole. If, at every board meeting, independent directors are given time to talk only to one another—with no company executives in the room—they can have more candid discussions about topics that would be difficult to address otherwise: for example, the CEO’s well-being. By making independent-directors-only discussions a regular part of board meetings, these honest conversations can take place without creating any tensions among the broader group that might arise if, say, the nonexecutive directors scheduled separate, ad hoc meetings on their own.

- Appoint a chair who can facilitate effectively. Board meetings can be stressful, particularly if an organization is not performing well, and the stakes of these discussions are often high. From CEO hiring and firing to M&A deals and plans for contending with unsatisfied shareholders, the very nature of board responsibilities requires directors to make decisions on difficult topics, and with limited time for discussion. The board chair plays a critical role in ensuring that meetings are both efficient and effective. To do so, the chair must create a clear agenda that balances fiduciary and strategic topics, encourage all board directors to voice their opinions, and effectively synthesize and summarize different perspectives to form a good basis for decision making.

These operating models and processes can help directors make the best use of the increasing time they spend on board work. We’ve seen that the boards that use these core operating models are better equipped to make valuable contributions to the organization and greater overall impact in the long term. Boards would do well to spend more of their time strengthening these core processes—and establishing the ones that aren’t yet in place.