Fuente: The Washington Post

Autor: Jena McGregor

When Kathy Higgins Victor first joined the board of directors at Best Buy in 1999, she was the only woman in the room. The former Northwest Airlines human resources chief and now president of a leadership coaching firm remembers how she “would say something, and then there’d be silence” followed by approval of a male colleague’s comments. She recalls thinking “Excuse me, was my mic off?”

Then there was the time an executive presented unflattering data about how female customers experienced shopping at the electronics retailer — not being acknowledged, not being helped — and her fellow directors rejected it, saying “that could not possibly be true.” Victor, meanwhile, thought the data was “spot on.”

Twenty years later, Victor is no longer the lone woman in Best Buy’s boardroom — she’s also part of the majority. After new CEO Corie Barry was elected to Best Buy’s board at its June shareholder meeting, the retailer became one of six companies in the Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index where women make up the majority of board members.

Since making a commitment five years ago to increase diversity — not only in gender and race but also in varying skill sets — Best Buy has added six board members, five of whom have been women. Four of the past five new directors have been people of color. “What I have seen is so much more diversity of perspective and such better decision-making outcomes,” said Victor, who also chairs the board’s nominating committee.

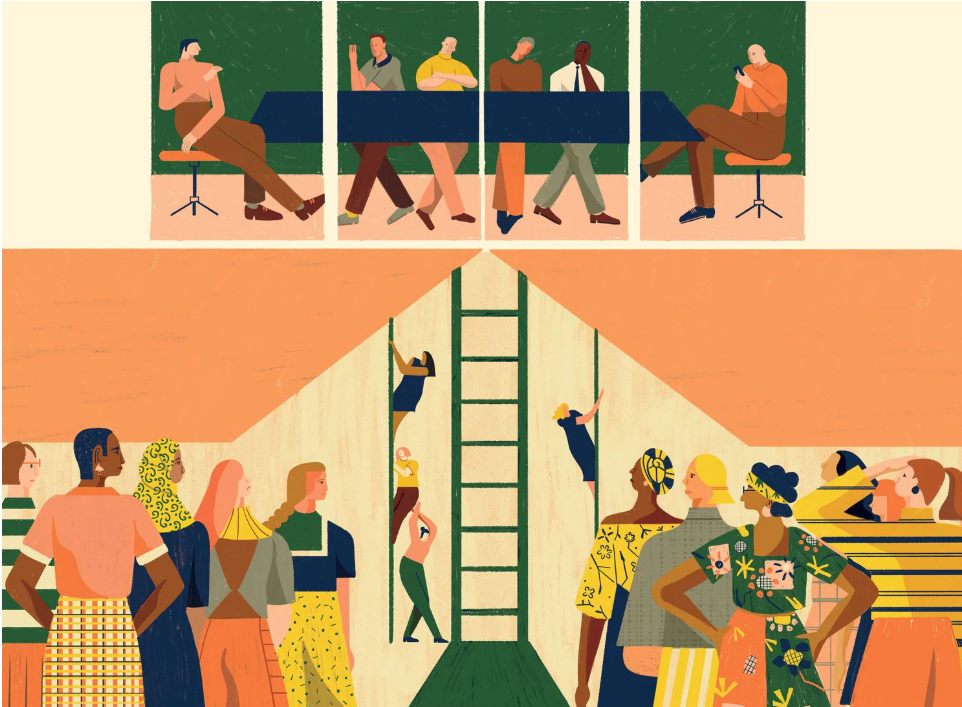

Though few boards have reached the same numbers, and the rate of change is still slow — Victor calls it a “glacial pace” — the percentage of women on boards has begun a steady march upward in recent years. The issue has grabbed the attention of investors, the media and lawmakers: The House Financial Services Committee even held a hearing last month about gender and racial diversity on boards.

After being stuck at 16 percent for several years, the percentage of women-held board seats in the S&P 500 now reaches nearly 27 percent, according to data from ISS Analytics, the data arm of the proxy adviser Institutional Shareholder Services.

Perhaps most notable is that all-male boards among S&P 500 companies have become a nearly extinct species. In 2009, there were 56 firms in the S&P 500 that did not include any women. As of June 28, there was one.

Copart, an online vehicle auction company based in Dallas, has the final all-male board in the S&P 500, according to data from ISS Analytics. But it has said it intends to fill a board vacancy with a “highly qualified, accomplished woman this year.”

In an emailed statement, Copart said it has had low turnover on its board but recognizes that it “would benefit from greater diversity that more accurately reflects that of our various stakeholders. … We also believe that achieving diversity objectives is an ongoing journey, not addressed by a single promotion or appointment.” The company said it considers diversity when evaluating board candidates and noted that it employs women in key management positions.

Yet that swift fall and near eradication of all-male boards among America’s largest publicly traded companies disguises the challenges ahead as boards try to move closer to parity. For one, the number of all-male boards is much higher among smaller companies: Among companies in the Russell 3000 index, which also includes smaller firms, 329 have no women on the board.

Practicing ‘twokenism’

Meanwhile, recent research has shown that boards tend to practice a sort of “twokenism,” diversifying to a point where they meet what’s considered the norm and then appear to do less to raise the numbers. Another study from 2013 found that first-time female directors — as well as minority directors — tend to receive far less mentoring about boardroom norms than white men, making other appointments less likely and shorter tenures by women or minorities more likely.

Gender is also, of course, only part of the diversity battle. A 2018 report from Deloitte and the Alliance for Board Diversity found that minority directors, whether male or female, make up 16 percent of Fortune 500 board seats. Gender diversity appears to get studied more frequently, perhaps because it seems more visible to researchers or clearer to track than race, which may not be as apparent from director bios or photographs.

Finally, some worry that so much emphasis on any link between gender diversity and financial performance could create heightened expectations. “What kind of pressure does that place onto shoulders of diverse directors?” said Aaron Dhir, an associate professor who studies corporate governance at York University in Toronto.

Though the shift in numbers and hitting a near-zero number of all-male boards among S&P 500 companies may be progress, “it’s frankly shocking that it’s 2019 and we’re only reaching that milestone now,” Dhir said.

The uptick in recent years has been driven by factors including increased scrutiny by investors and the fear of being called out in the media or by an advocacy group. “There are watchdogs that count how many women you have on boards or call you out if you have too few,” said Corinne Post, a management professor at Lehigh University who has studied the issue.

Other groups, such as TheBoardlist or the advocacy group Catalyst, have begun doing more to deliberately help match or refer women to board positions, acting as a talent marketplace or sponsorship program to help connect the two.

The number of proposals filed by shareholders on the topic of board diversity, meanwhile, has grown from eight in 2007 to 40 this year, according to ISS data. Major institutional investors have been talking about gender diversity in their voting guidelines: BlackRock has said it expects to see at least two women on the board, and State Street said it plans to vote against the entire nominating committee if the board remains all male.

Legislating diversity

Adding to the pressures, California passed legislation last year that will require public companies with their main offices in the state to eventually have between one and three female directors, depending on board size. A similar idea has been proposed in New Jersey.

Other experts attribute some of the growth to attention on research suggesting a link between more diverse boards and business results. Groups such as Catalyst have published reports on the topic. Studies from investment industry firms — as well as some academic and nonprofit papers — have also examined a link between diversity and factors such as lower acquisition costs, fewer financial restatements, the likelihood of more women in the executive ranks or higher return on equity.

“I think norms would not have changed nearly as much if there had not been this drumbeat that gender diversity on the board improves corporate performance,” said Katherine Klein, a management professor in the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania.

But Klein and other academics warn that the relationship between gender-diverse boards and financial performance is less clear than is sometimes touted. They argue that other explanations could be at play: Good financial outcomes could prompt boards to be more concerned about social norms and garner more resources to then hire more female directors. Variables such as firm size could also play a role.

Meanwhile, results from social science research are mixed, according to meta-analysis studies that review other research. One study found that the link between gender-diverse boards and financial performance “is inconclusive overall, with different studies finding positive, negative or no effects,” though more diversity was shown to be linked to more corporate social responsibility and ethical behavior.

Another review of 140 studies found that context matters. While it found the overall relationship between female board members and market performance “near zero,” it was positive in countries with more gender parity and negative in those with less. That study also found a positive relationship when it came to accounting returns (such as return on assets or return on equity) that became more pronounced in countries with greater shareholder protections. But even then, the positive link doesn’t necessarily mean diversity was what caused better performance.

Alice Eagly, a Northwestern University professor and a researcher on gender and leadership, said although there are good reasons to increase the number of women on corporate boards, the tie to better financial performance isn’t clear in rigorous social science research. “Women on boards are associated with enhanced social good,” Eagly said in an email. “This type of outcome of women in boards is far more reliable than improved firm financial performance.”

While some research results may be mixed, people who’ve served on boards or worked closely with them say they’ve seen the advantages to board diversity firsthand.

Holding directors accountable

Sallie Krawcheck, CEO of Ellevest, an investment platform for women and a former Wall Street executive, said: “As someone who’s been in board meetings, and been in senior leadership meetings, having a diverse set of individuals does change the conversation.”

Victor, too, said she has seen the effect. Had the same data about female customers’ experiences she heard 20 years ago been presented to today’s board, she said, it would have been “embraced.” And she believes that diversity in all its forms — gender, racial, expertise — has had an impact on financial performance.

“In the end, the people making decisions should look like the people affected by those decisions,” Victor said. “In our case, a board that is half women and substantially diverse from a people of color standpoint does that better than we once did.”

So what’s the best way to boost gender diversity on boards? Even the Government Accountability Office recently weighed in, publishing a report that coincided with the House committee hearing on board diversity. It calls for requiring a diverse set of underrepresented candidates, emphasizing the importance of diversity, looking beyond CEO candidates and adopting age or term limits — tactics many boards are already utilizing.

For her part, Victor believes that setting mandatory retirement ages or term limits on boards to increase the churn of long-standing male directors can be “arbitrary.” She said she thinks it’s “sad” that diversity has to be mandated and that there is potential such measures could prompt backlash.

But she is a fan of two things Best Buy does: The retailer requires that directors retire if for more than five years they’ve been out of the professional work that brought them to the board; and it holds directors accountable with yearly reviews, letting only those who make enough of a contribution stand for reelection.

“I’d like for us to work toward not having to talk about women directors or women leaders or people of color,” Victor said. “I’m hoping for a day we just talk about really effective directors.”