Fuente: Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance

Autor: Rusty O’Kelley, Justus O’Brien, and Laura Sanderson, Russell Reynolds Associates.

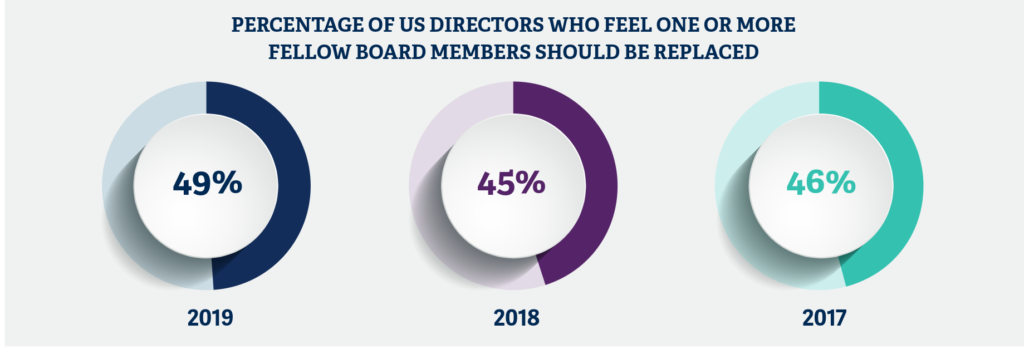

Many observers have been vocal in their perception of a decline in director quality in recent years. According to the 2019 PwC Corporate Directors Survey, 49 percent of US directors say one or more fellow board members should be replaced, and 23 percent say two or more should go. [1] These numbers are up from both 2017 and 2018. If that perception is true, then one must question why boards do not do a better job undertaking assessments and acting on their findings.

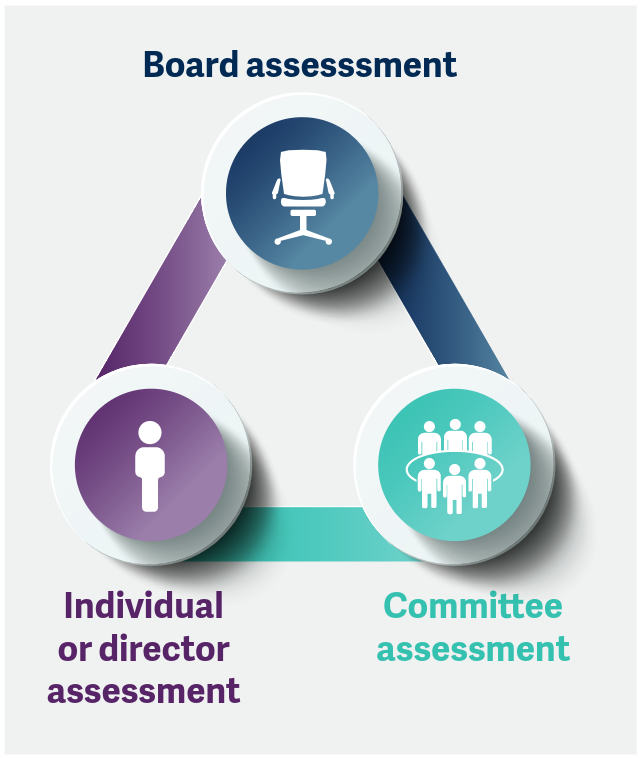

One issue to begin with is that not enough boards are doing impactful board and individual director assessments. While most companies have a mechanism for collective board assessment, just one in seven Russell 3000 companies, and fewer than one in three S&P 500 companies, have an annual review process for individual directors. The majority of boards are failing to fully implement even a basic approach to evaluating director performance. Unfortunately, among those that do, many use a survey-centric approach, with a director survey being the primary data-gathering effort. Directors often fail to give these surveys the real candor and insights required. The result is that a growing number of institutional investors and governance experts are acknowledging that assessments which rely primarily on electronic surveys are close to worthless.

Globally, Russell Reynolds Associates has conducted over two hundred board assessments over the past several years, each of which focused on multiple facets of board and director performance and drew upon multiple sources of data. In our experience, even well-run assessment processes (those that include director interviews and some level of benchmarking) often fail to connect board performance issues systematically and across multiple years. In too many countries, the board assessment is viewed simply as an annual event and not part of an integrated and on-going approach to enhancing board performance. We believe that boards need to shift away from a one-year-at-a-time “event” approach to a more substantive longer-term board assessment and review “system.” Developing a multiyear board assessment “system” can generate greater insights and impact and increase the opportunity for the board to support value creation.

“We believe good governance begins with a great board of directors. Our primary interest is to ensure that the individuals who represent the interests of all shareholders are independent, committed, capable, and appropriately experienced. … Boards must also continuously evaluate themselves and evolve to align with the long-term needs of the business.”

— Vanguard [2]

Defining what good looks like

In building a board and director assessment system, the board needs to clearly define what it means to be a high-performing board as well as a highly effective director. Based on Russell Reynolds’ research into director performance and board culture, we have identified five behaviors that the most effective directors exhibit:

- Being willing to constructively challenge management, when appropriate

- Possessing the courage to do the right thing for the right reason

- Demonstrating sound business judgment

- Asking the right questions

- Possessing independent perspectives and avoiding “groupthink” [3]

In the last year, Russell Reynolds conducted research to determine how boards and directors that are focused on long-term value creation are different from other boards. As has become increasingly clear, boards which established a shared focus on taking a long-term orientation to company performance produce above-average results (financial and otherwise). When it comes to individual directors, our research shows that “Long-Termers” are better informed about their company and industry than other directors. They have a higher level of understanding of organizational culture. And they are more likely to work between meetings, to come to discussions informed and prepared and to contribute expertise during board meetings.

From a process to a system

As governance and legal codes have evolved around the world, board assessments have become an increasingly important element of measuring and improving board performance. Performance-focused boards have developed robust processes to evaluate individual director and collective board performance over longer time horizons. Today, many of the best boards are increasingly looking for a broad, independent perspective and are working with outside advisors on these assessments. It is already an expectation of the UK Corporate Governance Code that companies will undergo an externally facilitated effectiveness review once every three years, and this requirement is also widely

viewed in other jurisdictions (including Australia, Brazil, France, India and Japan) as an indicator of a board’s focus on continuous improvement. In the United States, externally led board assessments once every two to three years are increasingly common and are recognized as valuable by many institutional investors and governance experts.

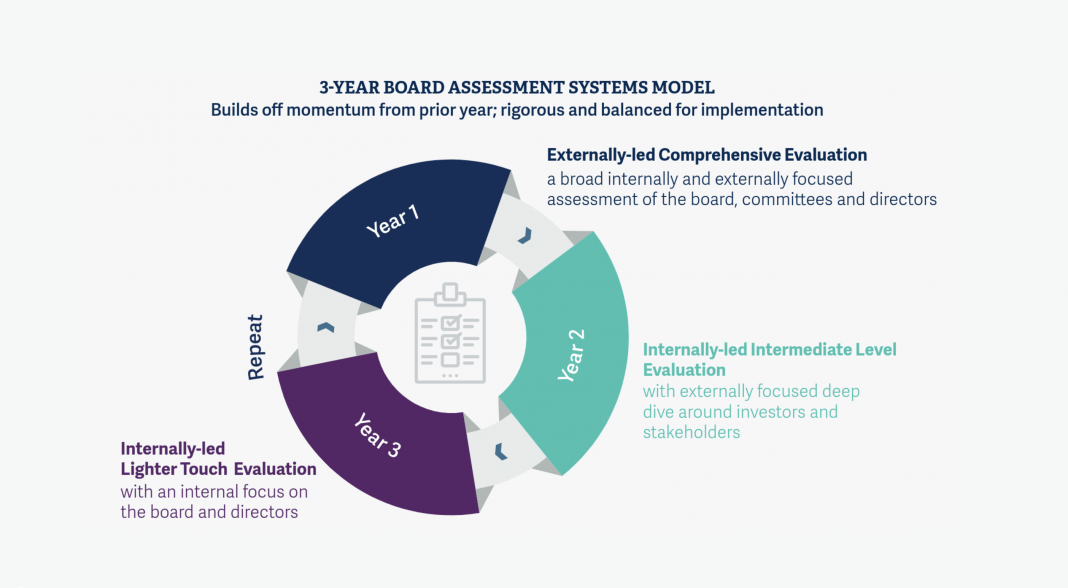

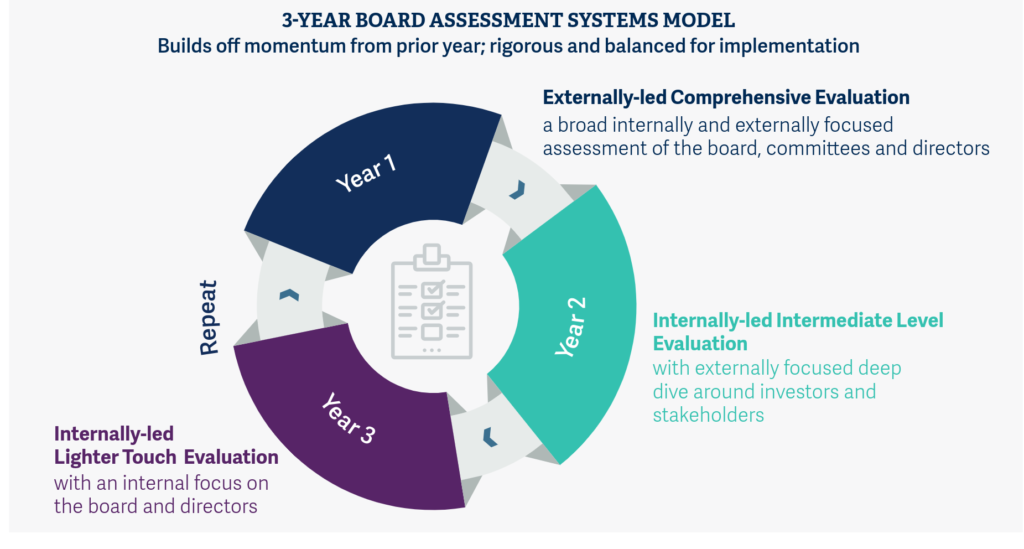

Russell Reynolds believes the next step to enhancing board performance and effectiveness is the development of a multiyear, integrated board and individual director assessment system. A systematic approach will telegraph to investors, regulators and other key stakeholders that the board is future-oriented and performance-focused. It will drive board quality and performance by ensuring multiple aspects of collective and individual performance are being evaluated and analyzed—and, ultimately, that all of the “dots” are being connected. While each board will undertake its assessment from a different starting point depending on board custom, country or stock exchange–specific regulatory requirements, below is a foundational model for boards to tailor to their specific situation and regulatory expectations.

Year One: Comprehensive Evaluation (externally led)

As with any governance process, it is critical to start thoughtfully to maximize value during the overall effort. Kicking off this three-year process with a robust external assessment will give the board foundational data and insights upon which to then build. By using an external advisor in year one, the board gains governance expertise, insights into best practices, institutional investors’ priorities and independent benchmarking against peers and exemplar companies.

While boards should scope the first year’s work based on the company’s unique needs, the board should consider covering:

- Benchmarking against peer companies and companies with best-in-class governance

- Strategy and risk alignment among the board members and with management

- The board’s alignment with corporate purpose

- Environmental, social and corporate governance review (including human capital oversight and sustainability)

- People and composition

- Board and committee structures and processes

- Board and committee leadership

- Board culture

- Any local regulatory specific topics (e.g., board oversight of corporate culture)

The general counsel also should review local/country-specific regulatory or proxy disclosure changes. In addition to this collective view of board performance, the board should consider conducting individual director peer reviews. When paired with collective board assessment, individual director assessment can inform upcoming director succession or board refreshment efforts.

This broad scope of work provides the board with a road map for the next two years of work and gives the board perspective on a broad range of key governance and performance issues. Based on our experience conducting full board and director assessments, key process steps include due diligence on the company and board; investor, peer and ESG benchmarking; electronic surveys (not as the primary process driver); in-person interviews with the board and (selected members of) management; and iteration and review of the report.

To drive impact, the most critical step is the full board agreeing on key priorities for the next two years with regular progress check-in points. Constructively sharing director feedback and specific recommendations will help drive performance improvement.

Year Two: Intermediate Evaluation (internally led)

The first-year assessment was internally and externally broadly focused in order to give the board a strong baseline of information and topics on which to focus for the coming years. The second year mainly focuses on gaining outside perspectives.

The focus should be on applying the lens of the company’s largest shareholders to the board, by both bringing in perspectives gleaned from the CEO, chair or lead independent director’s interactions with shareholders and also making use of investor surveys and comparing the board to each investor’s publicly stated governance preferences. Additionally, given investor’s focus on ESG and sustainability, it may be worth the board looking more deeply at priorities, actions, and disclosure around ESG. Similarly, it is helpful for the board to view its members through the eyes of potential activists. Ask yourself: If an activist focused on the company right now, what issues or concerns would they be most likely to raise? Similarly, are any individual directors more likely to raise the ire of activists?

In addition to gathering these outside views, the second year affords board leaders an opportunity to focus deeply on two to four issues raised in the first year’s assessment work. These will likely be the highest-priority items identified by board leadership and the CEO in the previous year. Additionally, the board can complete another director survey to continue gathering data. The general counsel should review any changes in relevant corporate law, governance code or proxy rules regarding governance.

Year Three: Lighter Touch (internally led)

The third year is intentionally a lighter touch compared to years one and two, and designed to reflect on progress and prepare for the next three-year cycle. Addressing the issues that arose during the prior assessments takes time and energy, and board leaders should be cautious not to burn out their board members.

The third year can continue with a short director survey as a check-in step. If there is capacity, the lead independent director or independent chair can also hold a series of individual director meetings to connect with them, hear their thoughts on what is working well or not and collect any other feedback that is on their mind. Additionally, the general counsel should review any changes in relevant corporate law, governance code or proxy rules regarding governance.

Repeating the system

On the planning side, board leaders should also take any steps needed to start the three-year cycle over again in the next year. Any scope or process refinements should be made to continuously improve the assessment system.

A growing need for external expertise and perspective

The expectations placed on boards continue to increase dramatically. There is greater scrutiny from investors, regulators, activists and other stakeholders as well as the media on the board’s quality, composition, ESG oversight and many other governance matters.

Over the past few years, several leadership advisory and executive search firms such as Russell Reynolds have built dedicated board advisory teams and centers of excellence around board culture, composition, investor governance expectations and ESG. Expert board advisors bring to the process extensive firsthand experience on board and governance matters. Those practices, such as the ones at Russell Reynolds and others, are often staffed with cross-functional teams of former management consultants, lawyers, institutional investors, proxy solicitors and current and former corporate directors.

While some directors may believe that outside advisors will be ineffective as a result of not knowing their board intimately, the opposite is actually true: These firms work with hundreds of boards and nominating committees annually, interviewing thousands of director candidates and placing the best ones on boards. They have generated a deep level of insight about board effectiveness and performance. When combined with the board composition and director search expertise, these firms provide a nuanced and expert view of board performance and individual director effectiveness. Additionally, these firms have continuing daily exposure to boardrooms and nominating committees around the world, which enhances their expertise. Their depth of experience working across numerous boards gives them a level of experience and broad perspective no “insider” would have.

While other advisors, such as law firms or accounting firms, are conducting some board assessments, they often struggle to understand the behaviors and characteristics of the best directors, the nuances of board culture, and the specific board leadership attributes that drive board performance and effectiveness. Those insights that are critical to evaluating board and director performance cannot be quickly learned. Law firms are expert at the legal disclosure issues and corporate law and are best utilized for those aspects of assessing boards.

“Board effectiveness reviews have become a more established practice globally …. However, LGIM finds they too often remain a box-ticking exercise. External review: We consider every three years to be best practice. An external review allows for an independent assessment of the board to be made by a fresh pair of eyes, with experience in assessing many other boards.”

— Legal & General Investment Management [4]

A time to act

It is concerning when any corporate director can look around the boardroom and say that one or more of their peers should be removed from the board. When almost half of directors in the PwC survey feel this way, it is a problem that must be addressed.

The one-year assessment process has outlived its usefulness as a corporate governance practice, and it is time for boards to transition to a multiyear systematic process that brings about real results—one where the majority of information won’t come from director surveys, but from real insights from multiple sources of perspective, information and data. This system should encompass performance, culture leadership and regulatory issues, and enable both the board and investors to chart progress over successive years. It should be a system that is an ingrained part of the board, leading to regular discussions around performance and impact and the role the board plays in governing the enterprise.