Fuente: Ethical Boardroom

Autor: By Alexandra Wrage, President at TRACE International

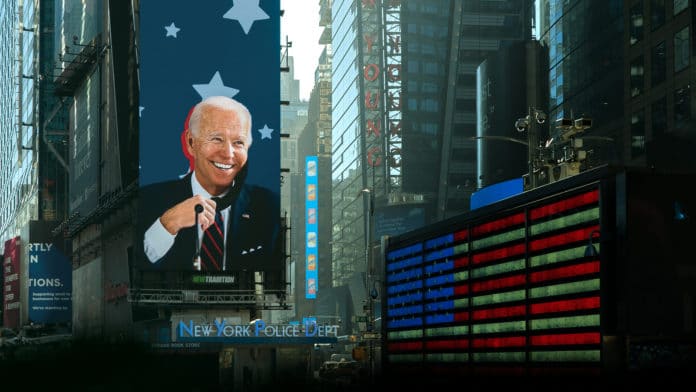

After it became clear that Joe Biden had won the US presidential election in November, investors rushed into environmental, social, and governance (ESG) exchange-traded funds, with almost $50billion added in mere days. This was a strong indication of market expectations that the Biden administration, with its promise to ‘build back better’ and plans for a ‘clean energy revolution’ and ‘environmental justice’, would be a champion of ESG, despite the lack of universal consensus on its definition.

These expectations stand in stark contrast to former President Trump’s posture. He questioned global warming, appointed climate change deniers to senior government positions, withdrew the United States from the Paris Agreement, stoked resistance to calls for racial justice and directed the US Department of Labor to change rules to curb pension fund managers’ ESG investments by banning the adoption of those funds as a default alternative for 401(k) defined-contribution retirement plans. Against this background, almost any new US president is bound to breathe more life into ESG. But beyond investor enthusiasm, what can we realistically expect from the Biden administration?

Defining ESG

American economist Milton Friedman wrote in the early 1960s that business’ only social responsibility is to increase profits, ‘so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition, without deception or fraud’.[1] Under the Friedman doctrine, social responsibility is solely the domain of individuals who ‘can do good – but only at their own expense’. He believed that ‘there are no social values, no social responsibilities in any sense other than the shared values and responsibilities of individuals’ in a society. When it is ‘appropriate for some to require others to contribute to a general social purpose whether they wish to or not’, Friedman believed it to be the domain of the political mechanism, through laws and regulations, rather than the responsibility of private enterprise.

Friedman allowed that corporate long-term self-interest and the legal framework may at times justify corporate spending on general social purposes, but couching such expenditures in social responsibility terms to generate goodwill for corporations was, to him, ‘hypocritical window dressing’.

We can question Friedman’s analytical starting point of denying that corporations can have true responsibilities before society because ‘a corporation is an artificial person’ with only ‘artificial responsibilities’. It can be argued that it is precisely because society bestows a legal fiction of ‘artificial person’ with its accompanying rights and benefits on private enterprise that society may impose social responsibilities on corporations.

Artificial persons are granted real benefits mostly unavailable to traditional human beings, such as limited legal liability; effectively unlimited copyright protection (no human can realistically benefit from copyright protection 95 years after a work’s publication); patent and trademark monopolies; corporate political rights and opportunities; and various new forms of government care, leniency and support. All these are at the disposal of these fictitious persons. Legal persons’ unique advantages lead to asset, wealth and power accumulation that used to be only within the grasp of hereditary monarchies. Yet, even the unqualified Friedman doctrine would permit modern ESG investment, based purely on its profit motive.

ESG is currently in vogue as a financial investment strategy based on the relatively recent notion that companies whose operations result in positive environmental, social and governance impact rival or exceed the risk-adjusted financial performance of those that have vague or negative ESG records. ESG investment strategy postulates that responsible, sustainable corporate practices pay off in a tangible return on investment by creating value rather than merely increasing cost, as Friedman supposed. Economists and financial observers insist that this is indeed true, especially at times of high market volatility.[2]

Furthermore, governments are beginning to borrow ESG framework for their policy and legislative initiatives. An EU regulation on ESG disclosures will come into effect 10 March 2021, requiring financial market participants and financial advisors to disclose how they integrate ESG factors into their risk processes and investment decision-making. UK financial service firms will have to disclose material impacts from climate change by 2025. The EU is considering legislation that would require companies to conduct environmental and human rights supply chain due diligence.

In some of the world’s top economies, Friedman’s ‘rules of the game’ are being redefined and expanded. Consequently, companies and investors must calculate the risk of ‘externality reversal’ as they are required in one way or another to pay for externalities they impose on society. On the positive side, companies that are seen as ESG champions stand to benefit in a number of ways beyond minimising risk, including increased consumer loyalty and goodwill, stronger government support, better market access and operating conditions, lower energy consumption and water intake, boosted employee motivation and talent attraction, and more.[3]

ESG Under The Biden Administration

As public trust in government, media and non-profits has eroded worldwide in the last year, business is the only institution maintaining public trust and seen by the public as both competent and ethical, according to the 2021 Edelman Trust Barometer.[4] It is certain that the Biden administration will have high expectations for business to play a larger role in addressing the crises and challenges facing the nation and the world.

Biden’s Focus on Climate Change

President Biden called climate change ‘the number one issue facing humanity’ and tapped John Kerry, former Secretary of State and 2004 presidential candidate, to be his climate czar on the world stage.

In another sign of his priorities, Biden nominated Martin Walsh to be his Labour Secretary. As Boston’s mayor, Walsh championed ESG by bringing the city’s ESG investments to $200million in the last two years.

Biden recommitted the United States to the Paris Agreement the day he was inaugurated and will seek to reclaim a global leadership role for America on climate change. In particular, Biden’s ambitious plans include eliminating carbon dioxide emissions from the grid by 2035 and ensuring that the country reaches net-zero emissions by 2050. We can expect climate change to shape every aspect of the new administration’s foreign policy, trade and national security strategies.

One of Biden’s stated goals is to make polluters pay for the environmental damage they cause and to promote green energy. Indeed, the greatest environmental costs arise from the use of carbon energy: a 2016 International Monetary Fund working paper estimated that externalities accounted for 78 per cent of the world’s $4.9trillion global fossil fuel subsidies in 2013.[5]

Even a small step toward shifting some of this to fossil fuel companies and other polluters could upend markets and the economy. But because the Democratic Party has only a slim majority in the US Senate – below the 60 votes needed to steer most legislation through the body due to filibuster rules – the Biden administration will face challenges as it seeks to secure legislative victories.

“THIS NEW BREED OF ACTIVISTS IS QUITE RARE STILL BUT THE LIKELIHOOD OF MORE SPAWNING IN THE COMING YEARS IS ALL BUT CERTAIN AND, AS COMPANIES PREPARE TO TURN A MORE ATTENTIVE EYE TO THEIR ESG STRATEGY, THEY SHOULD REMAIN AWARE THAT IF THEY LINGER TOO LONG, SOMEONE MIGHT SOON BE READY TO DO IT FOR THEM.”

Some policies, however, can be enacted unilaterally. With the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) coming under Democratic control, ESG regulatory reform will be within reach. We can expect securities disclosure rules to require at least some public companies to consistently measure and report their environmental impact and the financial risks caused by climate change. This will be a priority for the Biden administration, especially given the early leadership of the EU and the UK in this area.

Biden’s Focus on Human Rights

During his campaign, candidate Biden promised that ‘human rights will be at the core of US foreign policy’ for his administration. He has already indicated plans to reassess the US-Saudi Arabia relationship.

He has promised to be tough on China, referring to the Communist Party’s treatment of Uighurs as ‘genocide’ in 2020, long before the previous administration did.

Biden has promised to convene a Summit for Democracy early in his presidency – focussed in part on advancing human rights – that will include a call to action for the private sector. He is likely to continue the Trump-era practice of addressing human rights abuses abroad with sanctions; however, it is unlikely that the United States will soon join Europe’s push for mandatory human rights and environmental due diligence requirements in supply chains.

Biden’s domestic agenda will undoubtedly be influenced by the consequences of racial injustice the United States is reeling from. It is possible we will see publicly traded companies required to report their employee and management demographics and wage disparities by race, gender and other minority categories.

Biden’s Vision For The Future of ESG

Biden has signalled that he sees private entities playing a key role in addressing social and environmental challenges facing the United States and the world. With the EU and UK ESG disclosure and mandatory supply chain due diligence developments as a backdrop, we expect the concept of ESG to evolve from an inconsistent financial investment buzzword that is open to interpretation, into a more standardised measurement and disclosure compliance framework for publicly traded companies. At a minimum, we expect the SEC to impose standards on what constitutes ESG investments and to require US publicly traded companies to disclose the detailed basis for their ESG claims and scores.

How To Prepare

While so much remains to be seen, the private sector can prepare for the new ESG landscape in a few ways.

- An immediate first step that companies should take is to set the right tone at the top for championing ESG factors, making sure ESG functions are overseen by sufficiently senior executives with a seat at the management table and access to adequate resources.

- With the expected evolution of ESG from an investor/public relationship concern into a fully-fledged compliance and corporate risk management topic, companies can look to their anti-corruption compliance functions to see what might be expected of them. For example, enforcement authorities have repeatedly emphasised that anti-corruption compliance should be integrated into operational processes and not siloed off from them as an afterthought. ESG should similarly be integrated throughout the company. Just as check-the-box anti-corruption compliance programmes are discounted as ineffective, ESG programmes will be closely scrutinised for their effectiveness and signs of greenwashing.

- In anticipation of new rules and regulations, companies should conduct ESG risk assessments and tailor their approaches to specific ESG risks. At a minimum, companies should ramp up their capabilities for capturing, auditing and reporting data on their operations’ ESG factors.

- Companies can rely in part on their existing anti-corruption and other regulatory compliance processes and resources to find synergies and increase efficiency. For example, companies can use their third-party anti-bribery due diligence mechanisms to assess their exposure to environmental and human rights issues.

In the next few years, the private sector will become more deliberate and purposeful about its social and financial influence. Governments will introduce new requirements and actively enforce them. And consumers and civil society will demand tangible change.

We should accept and welcome that ESG is a permanent part of the new compliance landscape and prepare accordingly.